Formal Languages and Automata

Zhengfeng Ji

Lecture 1: Formal Languages and Automata

About This Course

Welcome

This is an incomplete set of notes prepared by Zhengfeng Ji for the course. Please do not distribute.

Formal languages and automata

Lecturer

Zhengfeng Ji

Office: 1-707, Ziqiang Technology Building

Email: jizhengfeng@tsinghua.edu.cn

Research direction: quantum computing, theory of computing.

Teaching assistants

Huiping Lin (lhp22@mails.tsinghua.edu.cn)

Aochu Dai (dac22@mails.tsinghua.edu.cn)

Shenghan Gao (sh-gao24@mails.tsinghua.edu.cn)

Third time I teach this course in Tsinghua

Your feedback is welcome

Computation and mathematics

Also known as Introduction to the ToC in some universities

Key observation

Computation, Mathematics, Logic

Computational problems, devices, and processes can be viewed as mathematical objects.

One interesting connection between computation and mathematics, which is particularly important from the viewpoint of this course, is that mathematical proofs and computations performed by the models we will discuss throughout this course have a low-level similarity: they both involve symbolic manipulations according to fixed sets of rules. (Watrous lecture notes)

We will study different types of recursions, Kleene star, context-free grammars, and Turing machines.

What you will learn in this subject

- Finite automata and regular expressions

- Pushdown automata and context-free grammars (CFG)

- Turing machine and computability, basic complexity theory

More importantly, we hope that you will learn how to write definitions/proofs rigorously;

Improve mathematical maturity.

I offer a follow-up course next semester called Introduction to Theoretical Computer Science, which covers lambda calculus, advanced computability, complexity theory, probabilistic computation, cryptography, and propositions as types.

See lecture notes at http://itcs.finite-dimensional.space

Teaching and learning

We use chalk and board.

The chalk and board way is better for teaching and learning theoretical subjects.

In How to speak from Patrick Winston (MIT), it is argued that chalk/board is the right tool for speaking when the purpose is informing.

Please be actively involved!

Reviewing after each class is highly recommended.

We will hand out notes after each class for you to review the materials covered in class.

The subject could be challenging for many of you.

It has a different style and different set of requirements.

Pause and think about the problem or theorem by yourself before you see the proof.

Barak: Even a five-minute attempt to solve the problem by yourself will significantly improve your understanding of the topic.

Textbook

Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation (3rd ed), by John Hopcroft, Rajeev Motwani, Jeffrey Ullman.

Hopcroft: In 1986, he received the Turing Award (jointly with Robert Tarjan) for fundamental achievements in the design and analysis of algorithms and data structures. He helped to build research centers in Shanghai Jiaotong and Peking U.

Motwani: Gödel Prize for PCP theorem. Author of another excellent textbook Randomized Algorithms. Youngest of the three. But unfortunately, he passed away in 2009.

Ullman: Turing award (2020) for his work on compilers. Author of the Dragon book Compilers: principles, techniques, & tools. He was the Ph.D. advisor of Sergey Brin, one of the co-founders of Google.

- Other materials:

- Introduction to the Theory of Computation, Michael Sipser

- Watrous lecture notes (https://cs.uwaterloo.ca/~watrous/ToC-notes/)

- Lecture notes: http://fla.finite-dimensional.space

Homework

About 12 assignments

Highly recommended to complete them on time

Grading

Mid-term: 20%

Attendance & homework: 10%

Final exam: 70%

Q & A

Online: Wechat group, learn.tsinghua.edu.cn, email

Office hour: 4-5 pm Tuesday

Why Learning This Subject

Ancient materials (mostly developed between 30's and 60's)

Finite automata

Simple examples of finite automata

Simple model enables deep understanding of its properties and efficient algorithms for manipulating it.

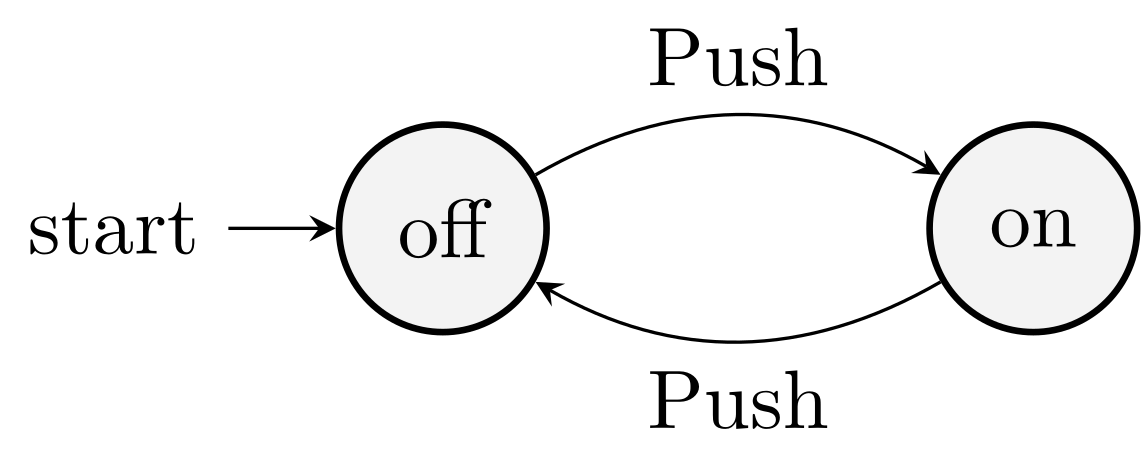

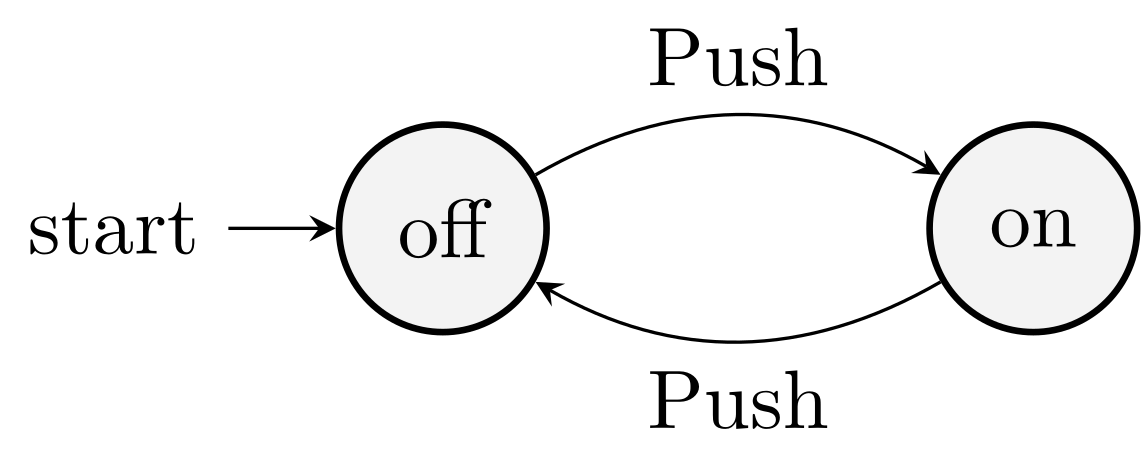

Example 1. Figure 1.1, push a button and switch between on and off, starting from off.

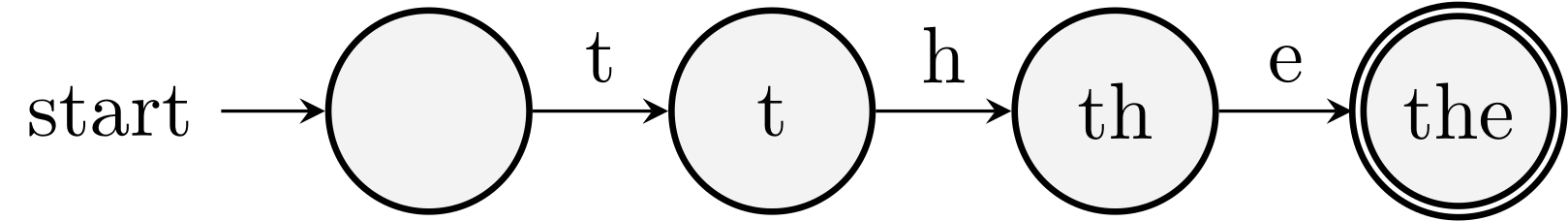

Example 2. Search for the word the

Finite automata are a valuable model for many important kinds of hardware and software.

- Specification, verification, and model checking of systems of finite states, circuits, and communication protocols

- Lexical analyzer for compilers

- Text search

When and how is it discovered

[McCulloch and Pitts, A logical calculus of ideas immanent in nervous activity, 1943]

[Kleene, Representation of events in nerve nets and finite automata, 1956]

[Rabin and Scott, Finite automata and their decision problems, 1959]

Regular expression

\([A-Z][a-z]*\) matches Computer

Context-free grammars

Grammars are useful models when designing software that processes data with a recursive structure.

Program languages

Compilers never enter a dead loop.

Pushdown automata

Machine with a single stack.

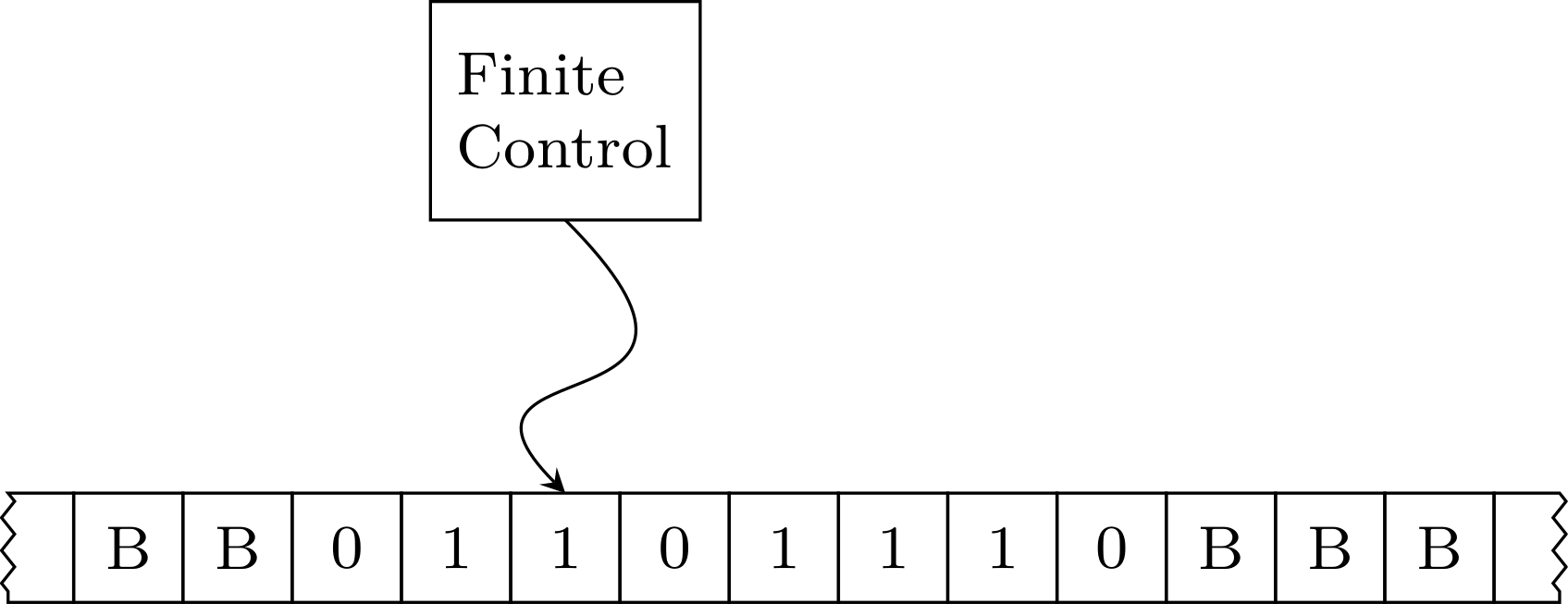

Turing machine

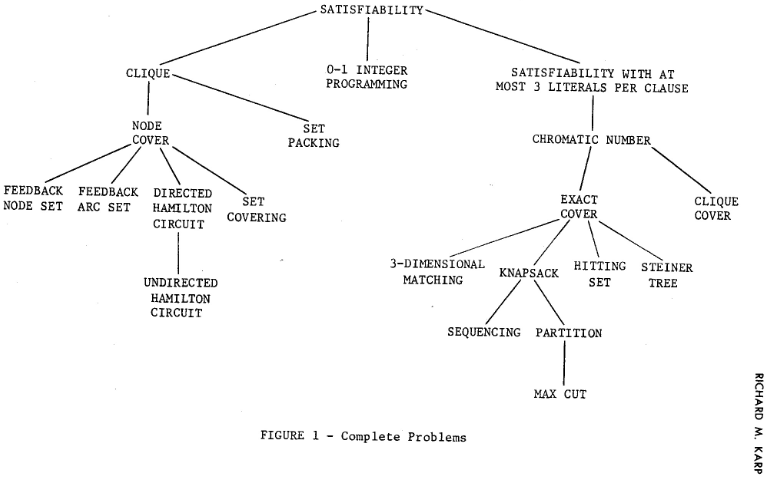

What can a computer do at all?

Hilbert 1928 Entscheidungsproblem (cf. Hilbert 10th problem about Diophantine equations)

The problem asks for an algorithm that considers, as input, a statement and answers Yes or No according to whether the statement is valid.

What cannot be done on a computer?

We must know. We will know.

The epitaph on his tombstone in Göttingen consists of the famous lines he spoke after his retirement address to the Society of German Scientists and Physicians on 8 September 1930.

What is computation?

Church: Lambda calculus (\(\lambda x . x^2 + 2\))

Gödel: Recursive functions

Turing: Turing machines (age 24)

You: C, Python, Java, …

TM is intuitive capture of computation, and Gödel is convinced.

It's like waiting for the bus. We waited for 2000 years for a formal definition of computation; three buses come along at the same time.

All equivalent: Is mathematics invented or discovered?

Church-Turing thesis

Logic and computation

Gödel's incompleteness: The first incompleteness theorem states that no consistent system of axioms whose theorems can be listed by an effective procedure (i.e., an algorithm) is capable of proving all truths about the arithmetic of natural numbers.

What can a computer do efficiently?

Space/time-bounded TMs

Extended Church-Turing thesis

Basics of FL&A

Sets and countability

The naive set theory treats the concept of a set to be self-evident. This will not be problematic for this course, but it does lead to problems and paradoxes—such as Russell's paradox—when it is pushed to its limits.

Bertrand Russell Russell's paradox. Let S be the set of all sets that are not elements of themselves: \(S = \{T : T \text{ is not in } T\}\). Is it the case that \(S\) is an element of itself? (Self-reference)

The size of a finite set \(S\) is denoted \(\abs{S}\).

Sets can also be infinite.

Definition. A set \(A\) is countable if either (i) \(A\) is empty, or (ii) there exists an onto (or surjective) function of the form \(f : \mathbb{N} \rightarrow A\). If a set is not countable, we say it is uncountable.

Power sets:

\(2^A\) or \(P(A)\)

More generally: What is \(A^B\)?

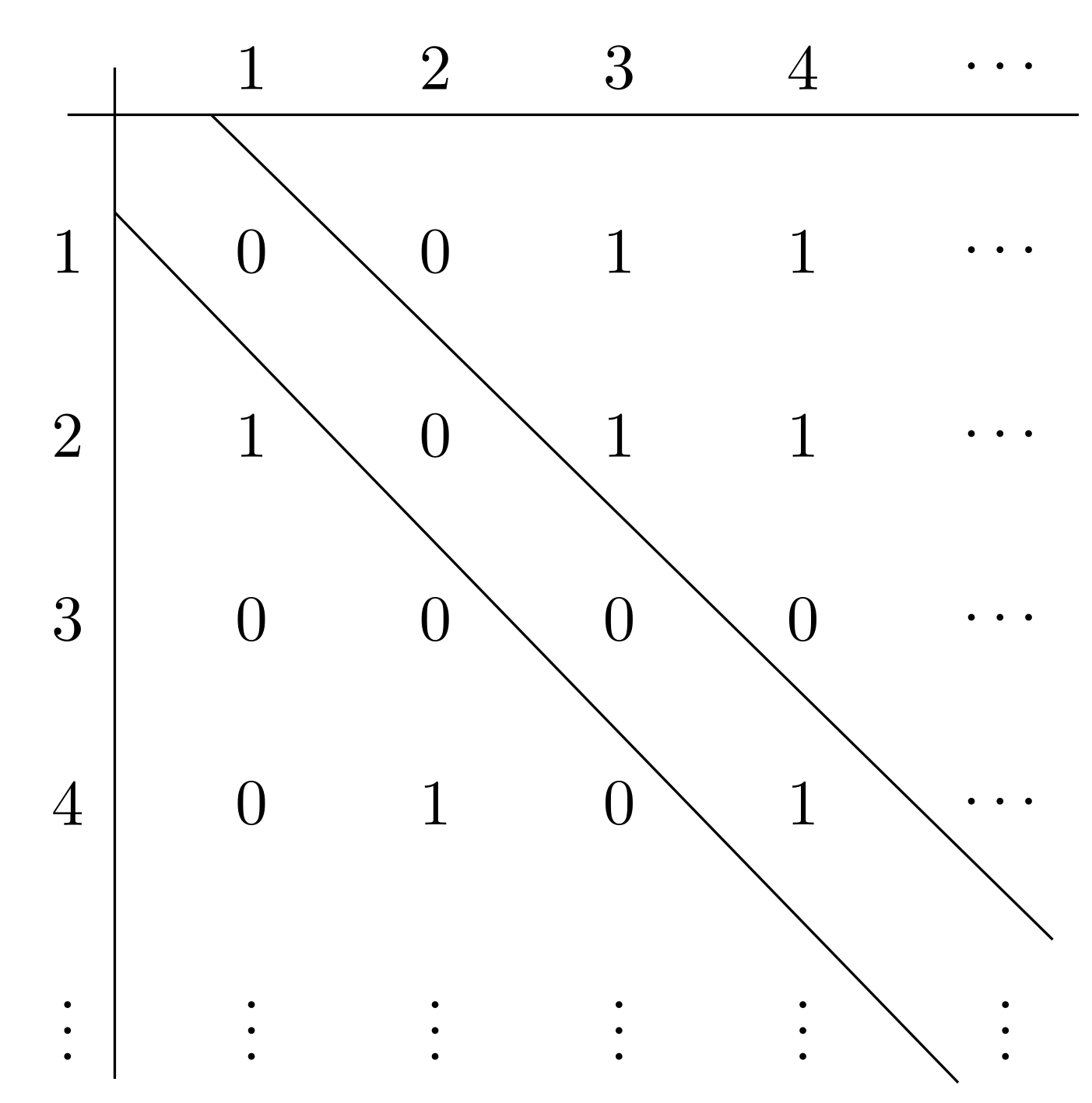

Theorem. The set \(\mathbb{Q}\) of rational numbers is countable.

Theorem (Cantor). The power set of the natural numbers, \(P(\mathbb{N})\), is uncountable.

There is a technique at work in this proof known as diagonalization. It is a fundamentally important technique in the theory of computation, and we will see instances of it later.

Central concepts of formal languages

Alphabets

An alphabet is a finite nonempty set of symbols.

\(\Sigma = \{0,1\}\)

\(\Sigma = \{a, b, c, \ldots, z\}\)

Strings

Strings are sequences of symbols chosen from an alphabet.

0101 is a seq from the alphabet \(\{0,1\}\)

Empty string: \(\eps\)

The length of string \(\abs{010} = 3\)

powers of an alphabet

\(\Sigma^3\)

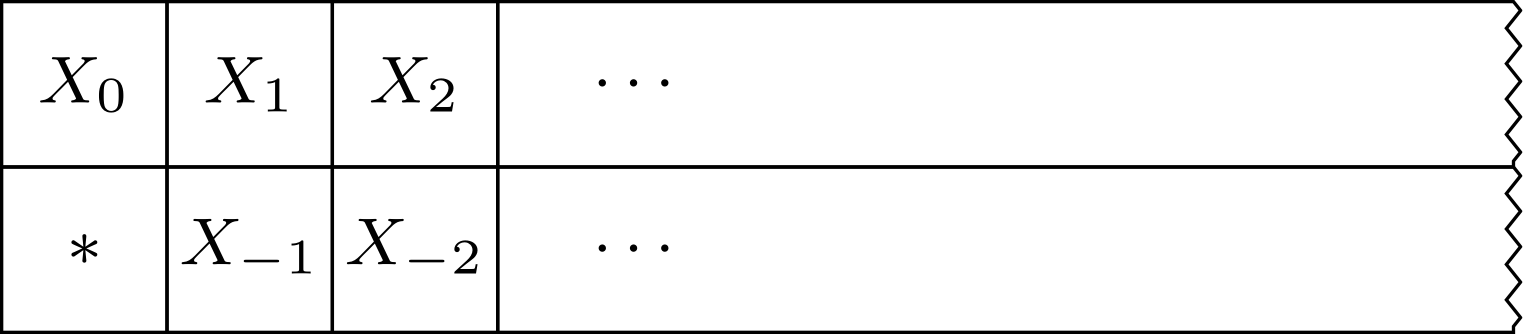

The set of all strings over an alphabet \(\Sigma^*\)

\(\Sigma^* = \cup_{n\ge 0} \Sigma^n\)

\(\Sigma^+\)

Concatenation \(xy\)

Language

Subset \(L\) of \(\Sigma^*\)

Set formers as a way to define languages

The set of binary numbers whose value is a prime

Problems

In automata theory, a problem is the question of deciding whether a given string is a member of some particular language.

Union/concatenation/closure (star, Kleene closure)

\(L \cup R\)

\(LR\)

\(L^* = \bigcup_{i=0}^\infty L^i\)

Proof techniques

Proofs about sets

Ex. \(R \cup (S \cap T) = (R \cup S) \cap (R \cup T)\)

Proofs by contradiction

Proofs by inductions

Inductive proofs

Prove a statement about \(S(n)\) for integer \(n \ge n_0\)

Basis: \(S(n_0)\) is true

Induction: if \(S(n)\) then \(S(n+1)\) for \(n \ge n_0\)

Mutual inductions

Prove statements together!

Example. In the on-off automata,

\(S_1(n)\): the automata is in the state off after \(n\) if only if \(n\) is even.

\(S_2(n)\): the automata is in the state on after \(n\) if only if \(n\) is odd.

Structural inductions

The most important proof technique for automata theory and programming languages

Ex. Trees

Basis: A single node is a tree, and that node is the root of the tree.

Induction: If \(T_1, T_2, \ldots, T_k\) are trees, then we can form a new tree as follows:

- Begin with a new node \(N\), which is the root of the new tree.

- Add copies of all the trees \(T_1, \ldots, T_k\)

- Add edges from node \(N\) to the roots of each of the trees \(T_1, \ldots, T_k\)

Theorem. Every tree has one more node than it has edges.

Proof. Use structral induction. Basis. The tree has a single node. Induction. Assume the claim is true for \(T_1, \ldots, T_k\), …

Ex. Expression

Basis: Any number or letter is an expression.

Induction: If \(E\) and \(F\) are expressions, then so are \(E + F\), \(E * F\), and \((E)\).

Reading

Lecture 2: Finite Automata

Outline

DFA, NFA, and \(\eps\)-NFA

An Informal Picture

Read Sec 2.1 of the textbook.

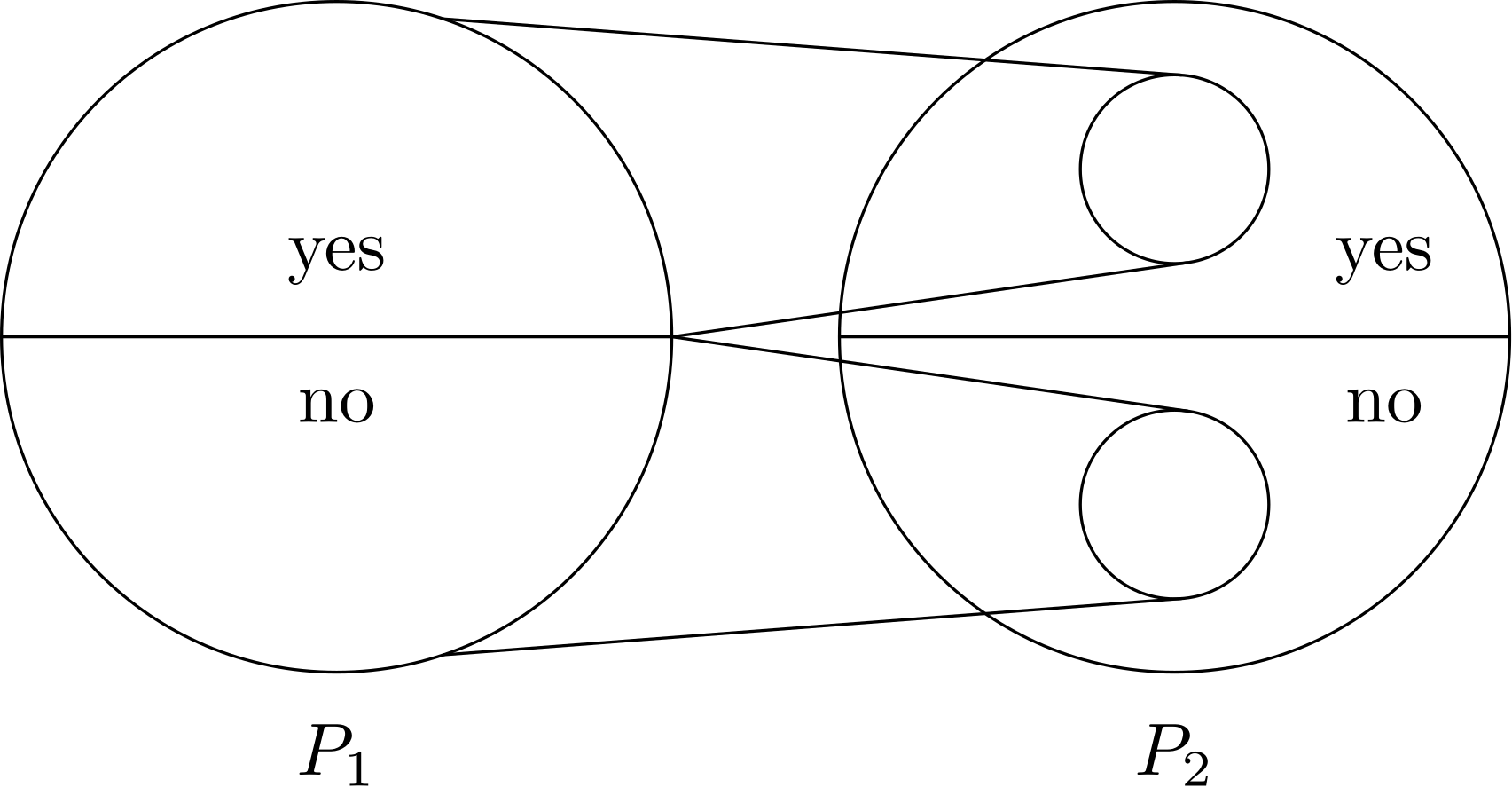

External actions drive the changes in the internal state.

What is a Finite Automata

Examples

Finite automata are very simple models of computation that will be our focus for the next four to five weeks.

Computation with finite memory

Example 1. A finite automaton for the light switch.

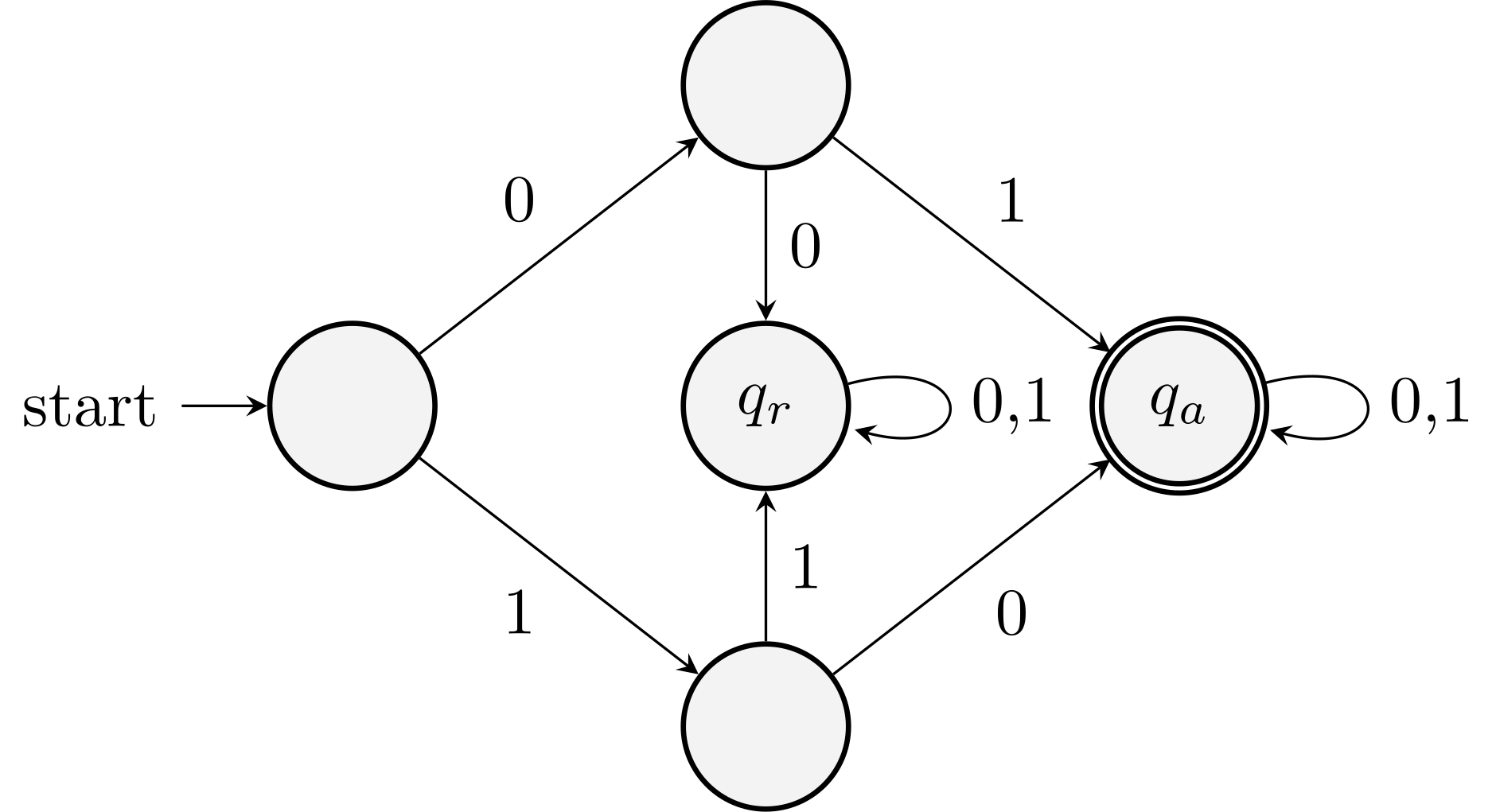

Example 2. A finite automaton for accepting all binary strings that has length at least two and the first two letters are different.

Example 3. A finite automaton for accepting all binary strings that are \(4 \pmod{7}\).

0 1 \(\rightarrow\) 0 0 1 1 2 3 2 4 5 3 6 0 \(*\) 4 1 2 5 3 4 6 5 6 We will talk about deterministic finite automata first.

Models we will not cover:

Mealy machines (outputs determined by the input symbol and current state)

Moore machines (outputs determined by the current state only)

Formal definition of DFA

Mathematical definition

- A finite set of states \(Q\)

- Input alphabet: A finite set of symbols \(\Sigma\)

- Transition function \(\delta : Q \times \Sigma \rightarrow Q\)

- A start state \(q_0 \in Q\)

- A set of final states \(F \subseteq Q\)

A deterministic finite automaton (DFA) is a five-tuple \(A = (Q, \Sigma, \delta, q_0, F)\)

Transition diagrams

See Examples 1 and 2.

They are best for visualization

Transition tables

Columns of state transitions

See Example 3 above.

They are machine friendly

How a DFA processes strings

It starts in the start state.

It enters a new state according to the transition function \(\delta\).

It accepts if and only if the final state is accepting.

Examples

Example. Design a DFA that accepts all and only the strings of 0's and 1's that have a \(01\) somewhere. That is, \(L = \{w \mid w = x01y \}\).

The automaton needs to remember:

- Has it seen a \(01\)? If so, accepts regardless of further input.

- Has it never seen a \(01\) but the most recent input is \(0\)?

- Has it never seen a \(0\)?

This gives us a simple automaton with three states.

Example. Design a DFA that accepts all and only the strings of 0's and 1's that have \(01\) as the last two letters. That is, \(L = \{w \mid w = x01 \}\).

Note the differences at the accepting node.

Example. Design a DFA that accepts all strings over \(\{0,1\}\) in which there are odd number of occurrences of 01.

For example, \(01000\) should be accepted while \(01001\) should not.

The language of a DFA

What do we mean by calling a language regular?

A language is regular if it is the set of strings accepted by a finite automata.

Regular: arranged in or constituting a constant or definite pattern, especially with the same space between individual instances.

Succinct and precise, and leaves no ambiguities

Extended transition function

How to define \(\hat{\delta}(q, w)\) for a string \(w\)?

Write \(w = xa\) and inductively define \(\hat{\delta}\).

We can write the language of the DFA using extended transition function: \(L(A) = \bigl\{w \mid \hat{\delta}(q_0, w) \in F\bigr\}\).

Are regular languages countable or not?

Yes!

This means that there are languages \(L \subseteq {\{0,1\}}^*\) that are not regular.

Nondeterministic Finite Automata

Nondeterminism

The machine can make guesses (non-deterministic choices) during computation.

Example

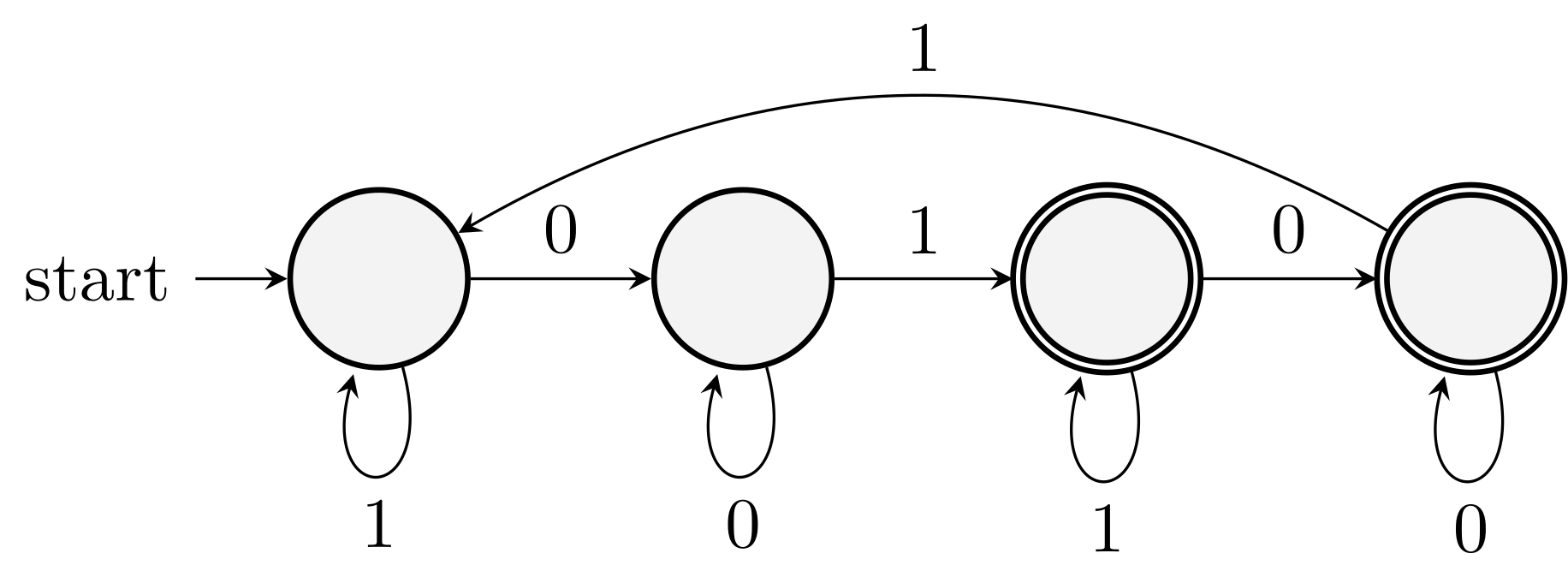

Binary strings whose 3rd letter from the end is a \(1\).

Example 2 with NFA:

Dead states and DFAs missing some transitions

They are not DFAs by definition, but they are in fact NFAs.

See Example 2.

Formal definition

It is still a five-tuple, but now the transition function is different. (The only difference)

Nondeterminism is reflected in the fact that \(\delta(q, a)\) is a set of states representing all possible target states when the current state is \(q\), and the input symbol is \(a\).

Extended transition function

- Write \(w=xa\) and take the union of \(\delta(p_i, a)\) for all \(p_i \in \hat{\delta}(p_0, x)\).

The language of an NFA

Intuition and formal definition: \[\begin{equation*} L(A) = \bigl\{w \mid \hat{\delta}(q_0, w) \cap F \ne \emptyset \bigr\}. \end{equation*}\]

The string is in the languages as long as there exists a nondeterministic choice of path leading to acceptance.

DFA and NFA Equivalence

What does it mean?

Any language \(L\) has a DFA if and only if it has an NFA.

The direction from DFA to NFA is easy as any DFA is a special NFA.

NFA to DFA: idea

Subset Construction

The transition in NFA is to a set of states (representing the nondeterministic choices).

Can we use a set of states (of the NFA) as the state of a DFA?

Transition: Union of target states for each state in the set.

NFA to DFA: proof

Let \(N\) be an NFA. We design a DFA \(D\) such that \(L(D) = L(N)\).

The five components of \(D\) are:

The set of states \(Q_D\) is the power set \(2^{Q_N}\).

The alphabet is the same \(\Sigma\).

The transition rule \(\delta_D\) is

\[\begin{equation*} \delta_D(S, a) = \bigcup_{q\in S} \delta_N(q, a). \end{equation*}\]

Start state \(\{q_0\}\).

Final states: any set that has nontrivial overlap with \(F\).

Now we need to show that the construction works, that is, \(w \in L(N)\) if and only if \(w \in L(D)\).

\(w \in L(N)\) means \(\delta_N(q_0, w)\) contains states in \(F\) and \(w \in L(D)\) means \(\delta_D(\{q_0\}, w)\) contains states in \(F\).

Induction on the length \(\abs{w}\) and prove that \(\delta_N(q_0, w) = \delta_D(\{q_0\}, w)\).

See Theorem 2.11 of the textbook.

Comments

DFA simulation of NFA could have exponentially large number of states.

Example: all bit strings whose \(n\)-th symbol from the end is \(1\).

Show that any DFA accepting those strings will have at least \(2^n\) states. (Pigeonhole principle)

Yet there is a NFA with \(n+1\) states for this. (The NFA first loops for a while on \(0,1\) and then move \(n\) steps sequentially).

Lecture 3: Regular Expressions and Languages

Finite Automata With Epsilon-Transitions

It is an NFA allowed to make a transition spontaneously without receiving an input symbol.

Why?

It has the same power as DFAs and NFAs.

But they are sometimes easier to use and construct, for example, when we discuss regular expressions.

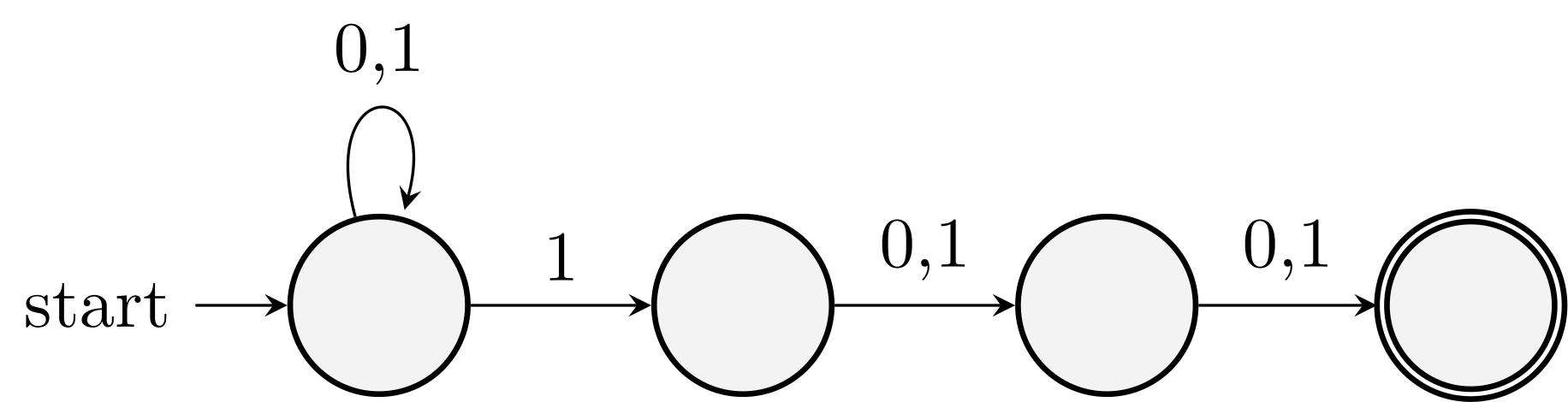

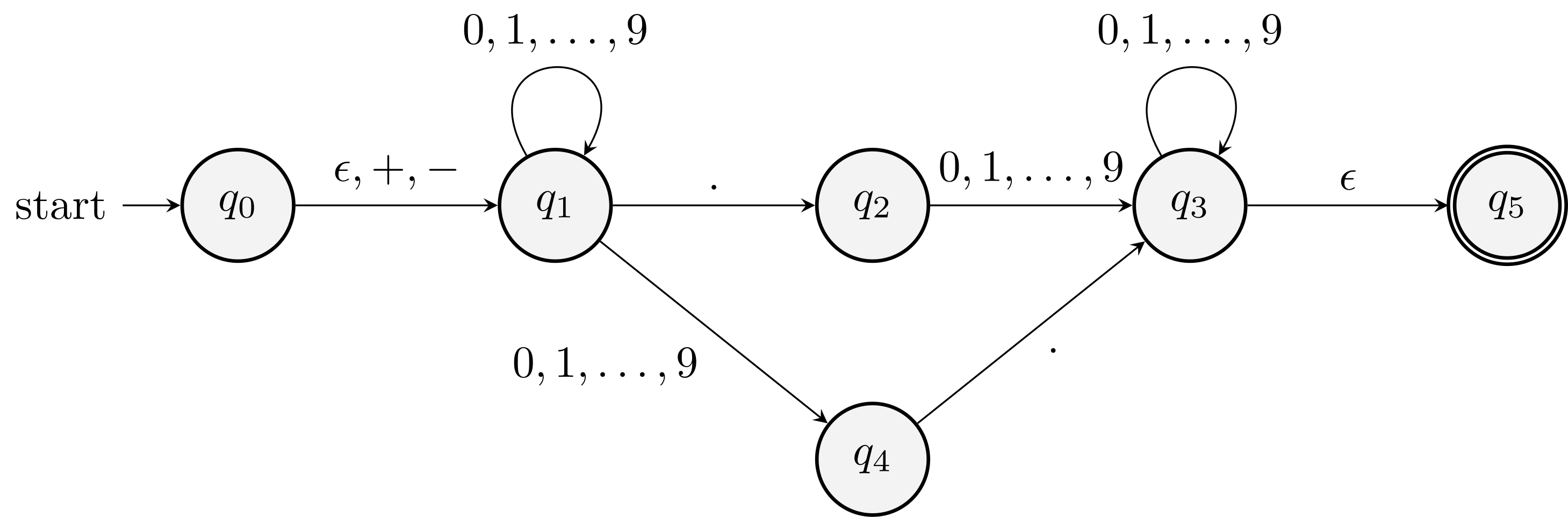

An example

Consider Example 2.18 of the textbook.

\(\eps\) \({+}, {-}\) \(.\) \(0,1,\ldots,9\) \(\rightarrow q_0\) \(\{q_1\}\) \(\{q_1\}\) \(\emptyset\) \(\emptyset\) \(q_1\) \(\emptyset\) \(\emptyset\) \(\{q_2\}\) \(\{q_1, q_4\}\) \(q_2\) \(\emptyset\) \(\emptyset\) \(\emptyset\) \(\{q_3\}\) \(q_3\) \(\{q_5\}\) \(\emptyset\) \(\emptyset\) \(\{q_3\}\) \(q_4\) \(\emptyset\) \(\emptyset\) \(\{q_3\}\) \(\emptyset\) \(*q_5\) \(\emptyset\) \(\emptyset\) \(\emptyset\) \(\emptyset\)

An \(\eps\)-NFA that accepts decimal numbers consisting of:

- An optional \(+\) or \(-\) sign

- A string of digits

- A decimal point

- Another string of digits. Either this string or the string in (2) can be empty.

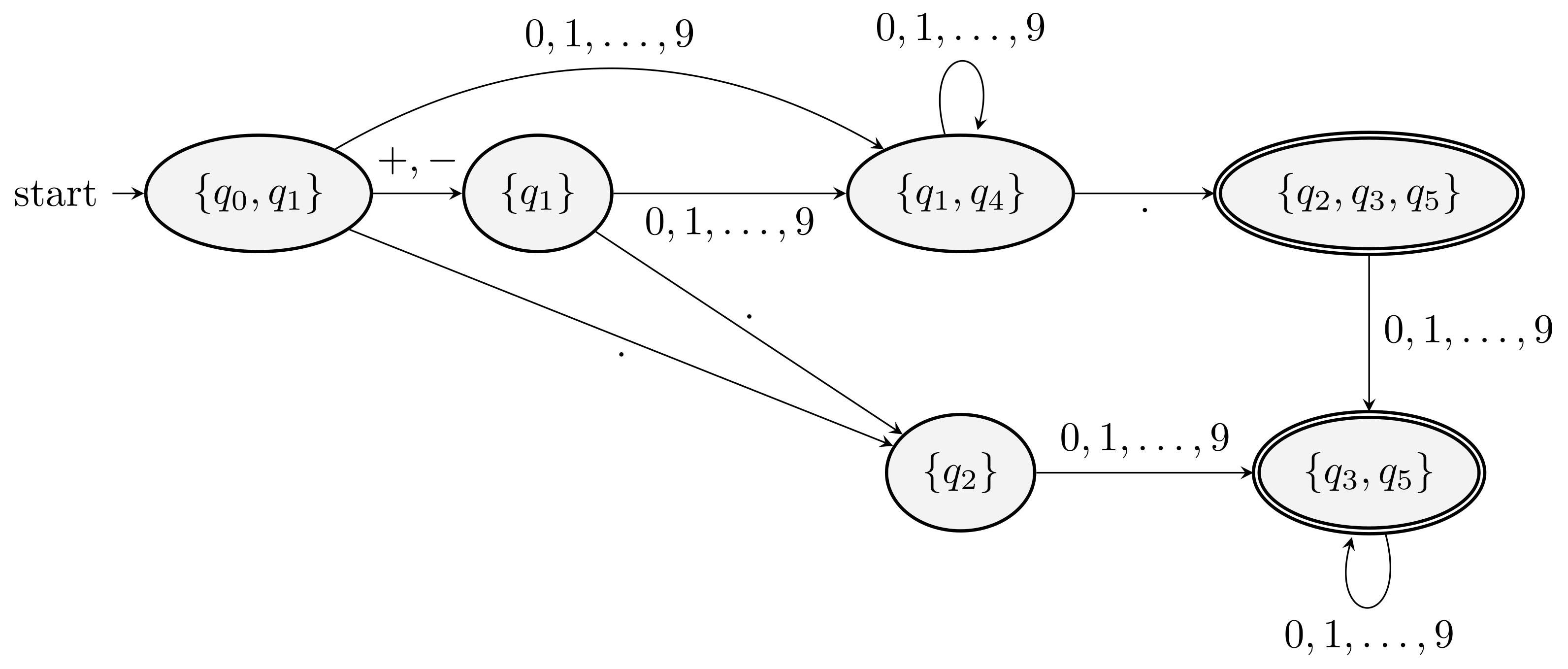

Compare it with the equivalent DFA.

Formal definition

Compared with the formal definition of NFA, now the transition function \(\delta\) takes a state and a member of \(\Sigma \cup \{ \eps \}\) as input.

\[\begin{equation*} \delta: Q \times (\Sigma \cup \{ \eps \}) \to 2^Q. \end{equation*}\]

Examples

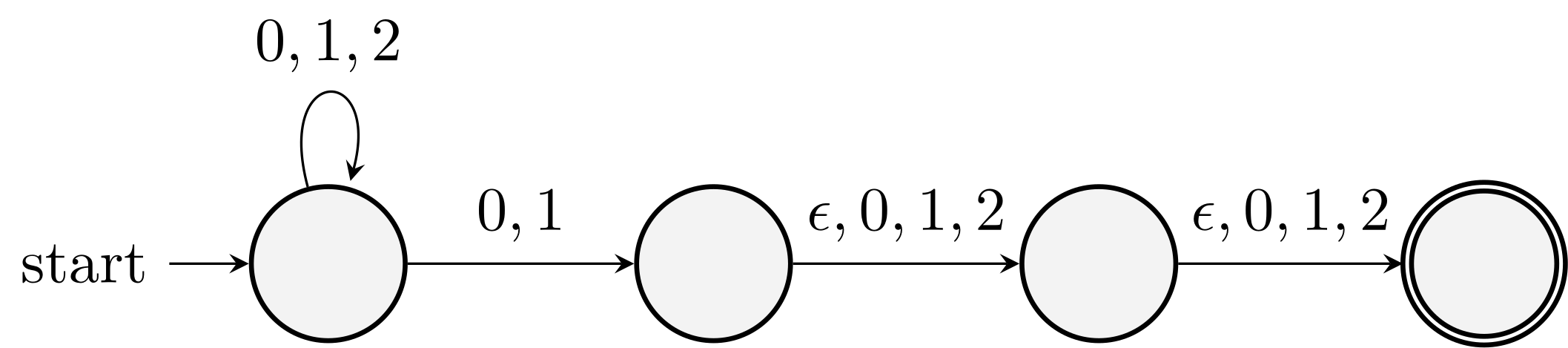

Example. Design \(\eps\)-NFA that accepts all strings over \(\{0,1,2\}\) whose length is at least one and one of the last three letters is not \(2\).

It means that there is a \(0\) or \(1\) in the last three letters.

Example. Design \(\eps\)-NFA that accepts \[\begin{equation*} \begin{split} L = & \{ w \mid w \in \{a,b,c\}^* \land \abs{w}\ge 4 \land\\ & \quad \text{ there is a } bac \text{ in the first five symbols of } w \land\\ & \quad \text{ there is a } acb \text{ in the last five symbols of } w \}. \end{split} \end{equation*}\]

Can you see there are three cases to consider?

Epsilon-closure ECLOSE(\(q\))

The key is to keep track of the possible current states of an automaton.

What is ECLOSE(\(q\)) informally?

Define it yourself.

If \(p, q\) in ECLOSE(\(r\)), do we always have ECLOSE(\(p\)) = ECLOSE(\(q\))? No!

The minimum set such that- \(q \in \text{ECLOSE}(q)\).

- If \(p \in \text{ECLOSE}(q)\) and \(r \in \delta(p, \eps)\), then \(r \in \text{ECLOSE}(q)\).

ECLOSE(\(S\)) is the union of ECLOSE(\(q\)) for \(q \in S\).

Example

- ECLOSE(\(q_0\)) = \(\{q_0, q_1\}\)

- ECLOSE(\(q_2\)) = \(\{q_2\}\)

Extended transition

Take an \(\eps\) move in the end.

Basis: \(w=\eps\), it is ECLOSE(\(q\)).

Induction: \(w=xa\)

- Take the \(x\) transition,

- Take the union with \(a\),

- Take the \(\eps\)-closure.

Eliminate \(\eps\)-transitions

For any \(\eps\)-NFA \(A\), there is a DFA \(B\) equivalent to \(A\). (Not that different from the equivalence of DFA and NFA)

- Compute the ECLOSE.

- Use the subset construction (with ECLOSE after each move)

Often times, you do not need all the subsets! Start from the initial state and generate the subsets one by one.

Example

The DFA obtained by eliminating the \(\eps\)-transitions in Example 2.18 is given in the figure above. For simplicity, the dead state and arrows to it are not shown.

The starting state is \(\text{ECLOSE}(q_0) = \{q_0, q_1\}\).

Regular Expressions

Now we switch our attention from machine-like descriptions of languages—deterministic and nondeterministic finite automata—to an algebraic description of the regular expression.

And show that they can describe all and only regular languages (languages accepted by finite automata).

It is a declarative way to express the strings we want to accept.

grep, lex

Regular expressions: Definition

- Basis: three parts

The constants \(\eps\) and \(\emptyset\) are regular expressions. \(L(\eps) = \{\eps\}\).

If \(a\) is a symbol, then \(a\) is a RE. \(L(a) = \{a\}\).

- Induction: four parts

- If \(E\) and \(F\) are RE, then so is the union \(E + F\). \(L(E+F)=L(E) \cup L(F)\).

- …, then so is the concatenation \(EF\). \(L(EF) = L(E)L(F)\).

- …, then so is the closure \(E^*\). \(L(E^*) = (L(E))^*\).

- …, then so is (E). \(L((E)) = L(E)\).

Examples

01 means \(\{01\}\)

01* means \(\{0, 01, 011, 0111, \ldots\}\)

(01)^* means \(\{\eps, 01, 0101, \ldots\}\)

Example. Write a RE for strings with alternating 0's and 1's.

\((01)^* + (10)^* + 1(01)^* + 0(10)^*\)

or

\((\eps + 1)(01)^*(\eps + 0)\)

Example. Write a RE for binary strings whose first and last letters are the same.

\(0(0+1)^*0 + 1(0+1)^*1 + 0 + 1\)

Example. Write a RE for binary strings where every pair of neighboring 0's occur before every pair of neighboring 1's.

Strings in the language can be partitioned into two parts where the left part has no 11, and the right part has no 00.

\((10 + 0)^* (\eps + 1)(01 + 1)^* (\eps + 0)\)

Precedence of regular expression operators

\(xy+z\)

Order: star, dot, union

Application of RE

Read Section 3.3 of the textbook.

Unix extension

The ability of name and refer to previous strings that have matched a pattern.

More about a way of writing RE succinctly.

- dot . stands for any character

- \([a_1 a_2 \cdots a_k]\) stands for \(a_1 + a_2 + \cdots + a_k\)

- range form [A-Za-z0-9]

- [:digit:], …

Notation

- | is used instead of +

- ? zero or one (\(R? = \eps + R\))

- + one or more (\(R^+ = RR^*\))

- {\(n\)} \(n\) copies of

Lexical analysis

else {return (ELSE);}

[A-Za-z][A-Za-z0-9]* {code to enter the found identifier to the symbol table; return (ID);}

>= {return (GE);}Finding patterns in text

Most editors support RE search and replacement.

Finite Automata and Regular Expression

Define exactly the same set of languages.

Perhaps the most important result in FA & RE.

DFA to RE

Kleene construction

Induction + Restrict the size + Consider expressions between multiple states

Probably the first non-trivial proof we see in this course.

Consider several languages together.

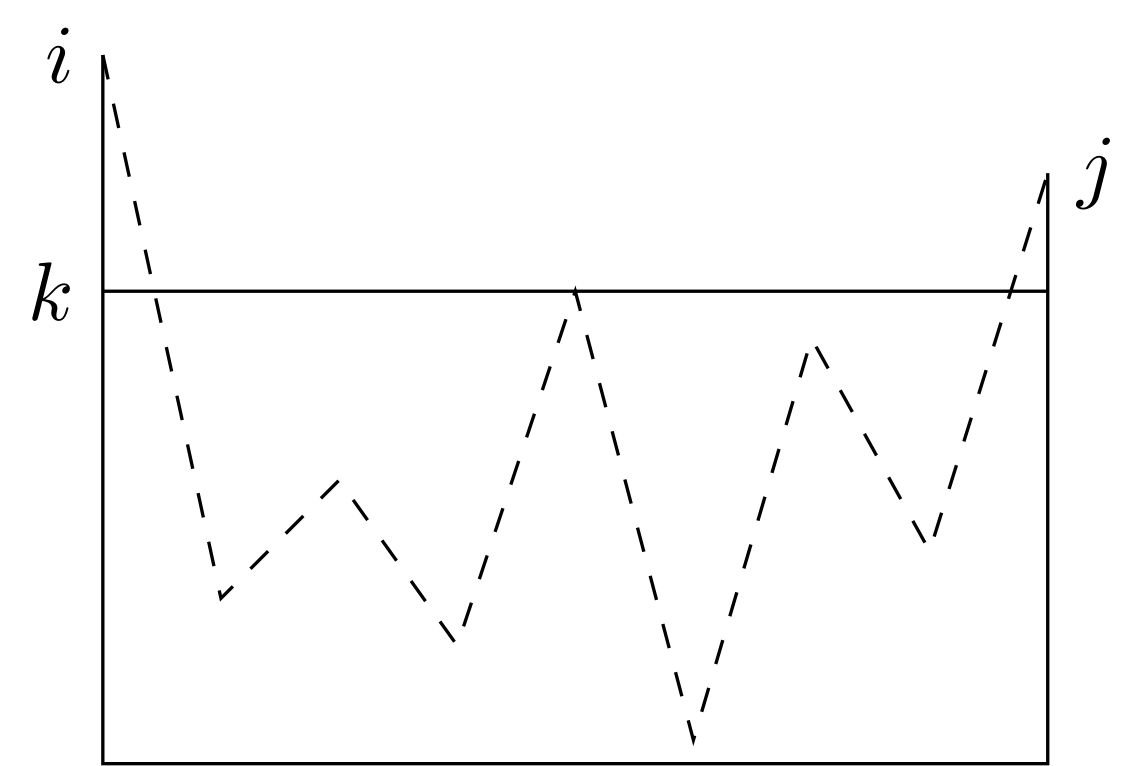

Idea: Roughly, we build expressions that describe sets of strings that label certain paths in the DFA's transition diagram. However, the paths can pass through only a limited subset of the states. In an inductive definition of these expressions, we start with the simplest expressions that describe paths that are not allowed to pass through any states. And inductively build the expressions that let the paths go through progressively larger sets of states.

Proof outline

Let the states be \(\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}\).

Let \(R^{(k)}_{ij}\) be the strings such that if we start from \(i\), we will end up at \(j\) visiting intermediate (not including \(i,j\)) states \(\le k\).

Basis: \(k = 0\). Since all states are numbered \(1\) and above, the restriction on the path is that the path must have no intermediate states at all.

There are two cases to consider.

- An arc from \(i\) to \(j\).

- A path of length \(0\) that consists of state \(i\) only.

If \(i \ne j\), then only case 1 is possible.

In that case, \(R^{(0)}_{i,j}\) is \(a_1 + a_2 + \cdots + a_k\) where there are transitions from \(i\) to \(j\) on symbols \(a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_k\).

If \(i = j\), consider all the loops from \(i\) to itself.

\[\begin{equation*} R^{(0)}_{ij} = \begin{cases} \eps & \text{no self loop},\\ \eps + a_1 + \cdots + a_k & \text{loops with } a_1, \ldots, a_k \end{cases} \end{equation*}\]

Induction: (on \(k\))

The path does not go through state \(k\) at all.

The path goes through state \(k\) at least once.

\[\begin{equation*} R^{(k)}_{ij} = R^{(k-1)}_{ij} + R^{(k-1)}_{ik} \bigl(R^{(k-1)}_{kk}\bigr)^* R^{(k-1)}_{kj}. \end{equation*}\]

The method works even for NFA.

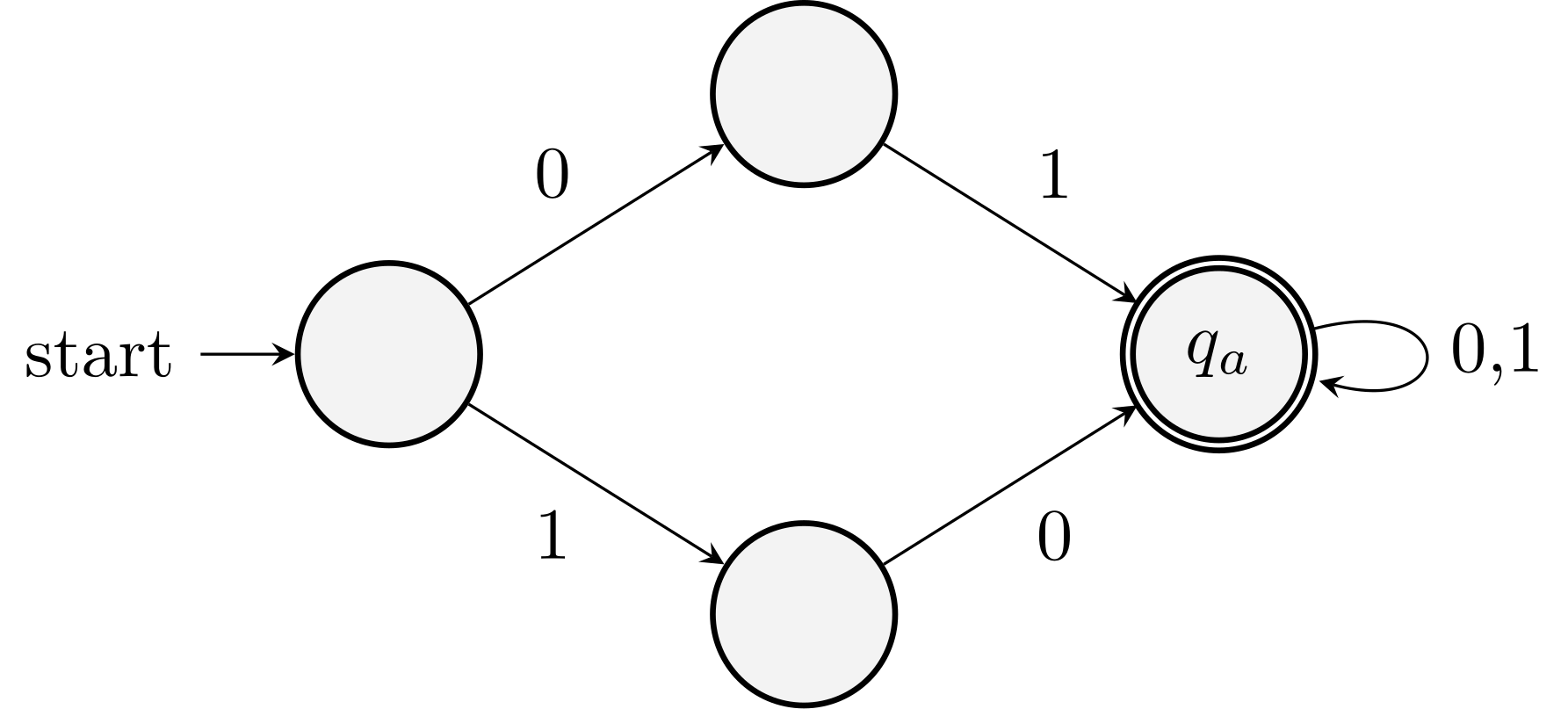

Example

Convert the DFA in the figure to a RE.

Some intermediate expressions are shown in the table.

Regular Expression \(R^{(0)}_{22}\) \(\eps + 0 + 1\) \(R^{(1)}_{12}\) \(1^*0\) \(R^{(1)}_{22}\) \(\eps + 0 + 1\) \(R^{(2)}_{12}\) \(1^*0(0+1)^*\)

Lecture 4: Finite Automata and Regular Expression

State Elimination Method

Converting DFA's to RE by eliminating states

- Issues for the above method:

- About \(n^3\) intermediate expression.

- The length of the expression could grow as \(4^n\) for an \(n\)-state automaton.

- Each \(R^{(k-1)}_{kk}\) was written in about \(n^2\) expressions.

Idea

The approach to constructing regular expressions we shall now learn involves eliminating states. When we eliminate a state \(s\) all the paths that went through \(s\) no longer exist in the automaton.

Automata with RE as labels!

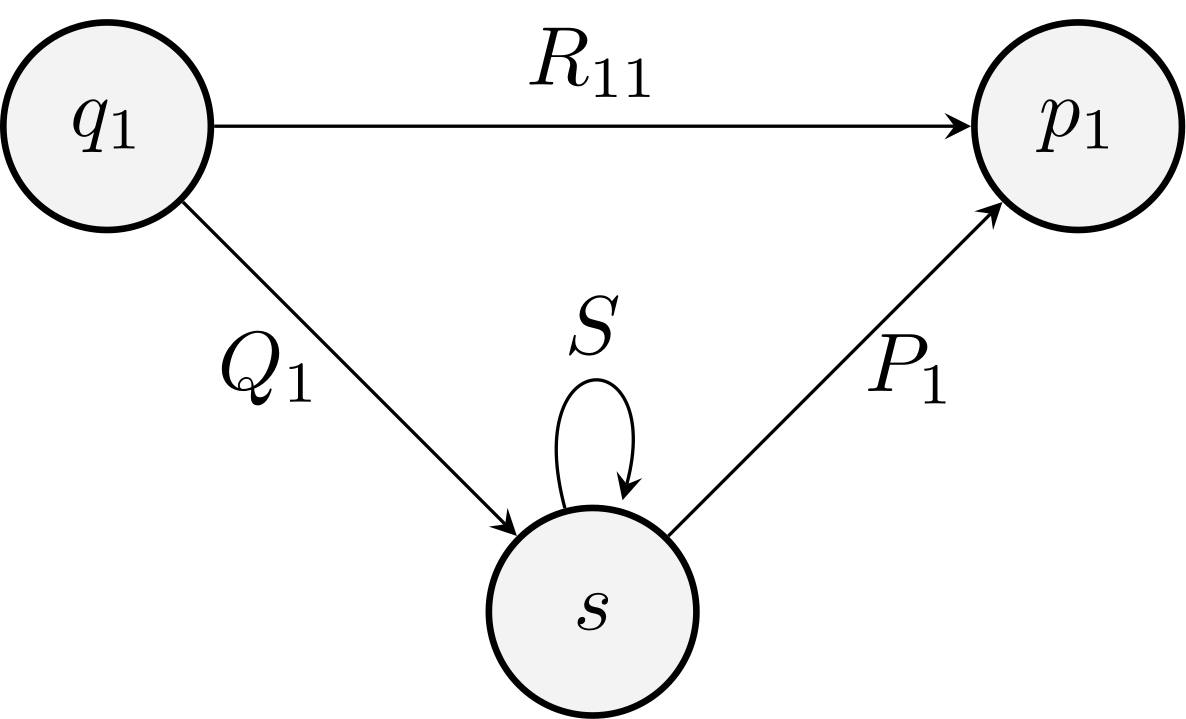

The eliminating method

Eliminate a state \(s\)

\(R_{11} + Q_1 S^* P_1\)

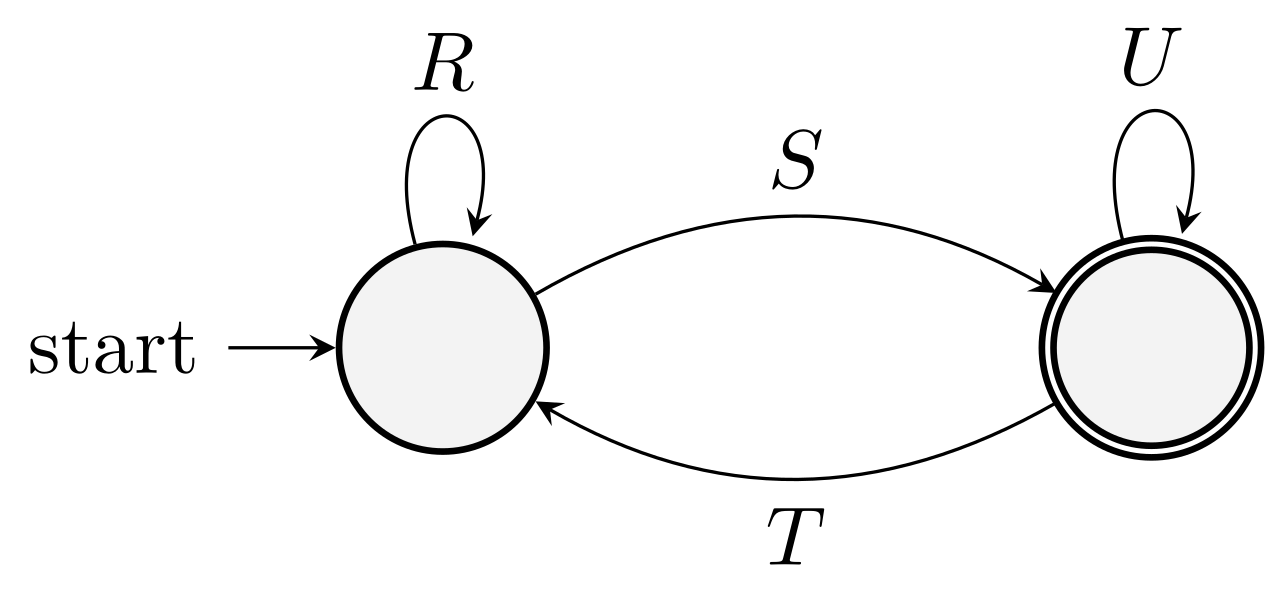

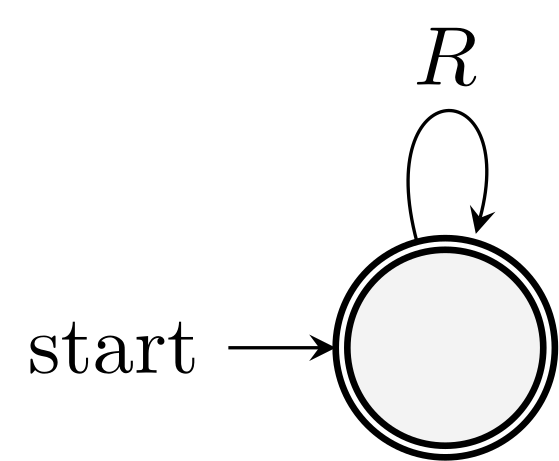

After the elimination, We will get a two-state or one-state automaton:

\((R+SU^*T)^*SU^*\)

\(R^*\)

State elimination procedure:

- For each accepting state \(q\), eliminate all but \(q\) and \(q_0\).

- Take the union.

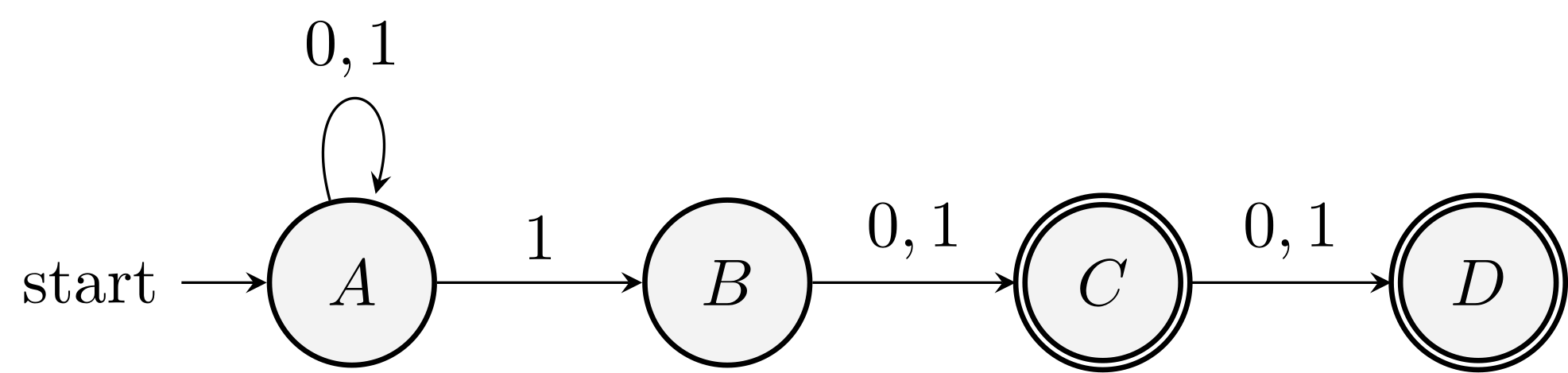

Example (Example 3.6 of the textbook)

An automaton accepts all strings whose second or third position from the end has a \(1\).

Step 1. Use RE as labels.

Step 2. Eliminate B. A to C is empty, \(1 \emptyset^* (0+1)\)

Then we branch (for all accepting states)

- First, consider those strings accepted at D. We eliminate C.

- Second, consider those strings accepted at C. We eliminate D. There is no arc added.

Final answer

\((0+1)^*1(0+1) + (0+1)^*1(0+1)(0+1)\)

From RE's to Automata

The language \(L(R)\) of RE \(R\) is also \(L(E)\) for some \(\eps\)-NFA \(E\).

Thompson method

Structural induction on \(R\).

Simplification: \(E\) satisfies the following three extra conditions:- Exactly one accepting state

- No arcs into the initial state

- No arcs out of the accepting state

(Note: 2 and 3 are used to avoid extra discussions in \(R^*\) construction)

Basis: Automata for accepting \(\eps\), \(\emptyset\), \(a\) satisfying the three extra conditions.

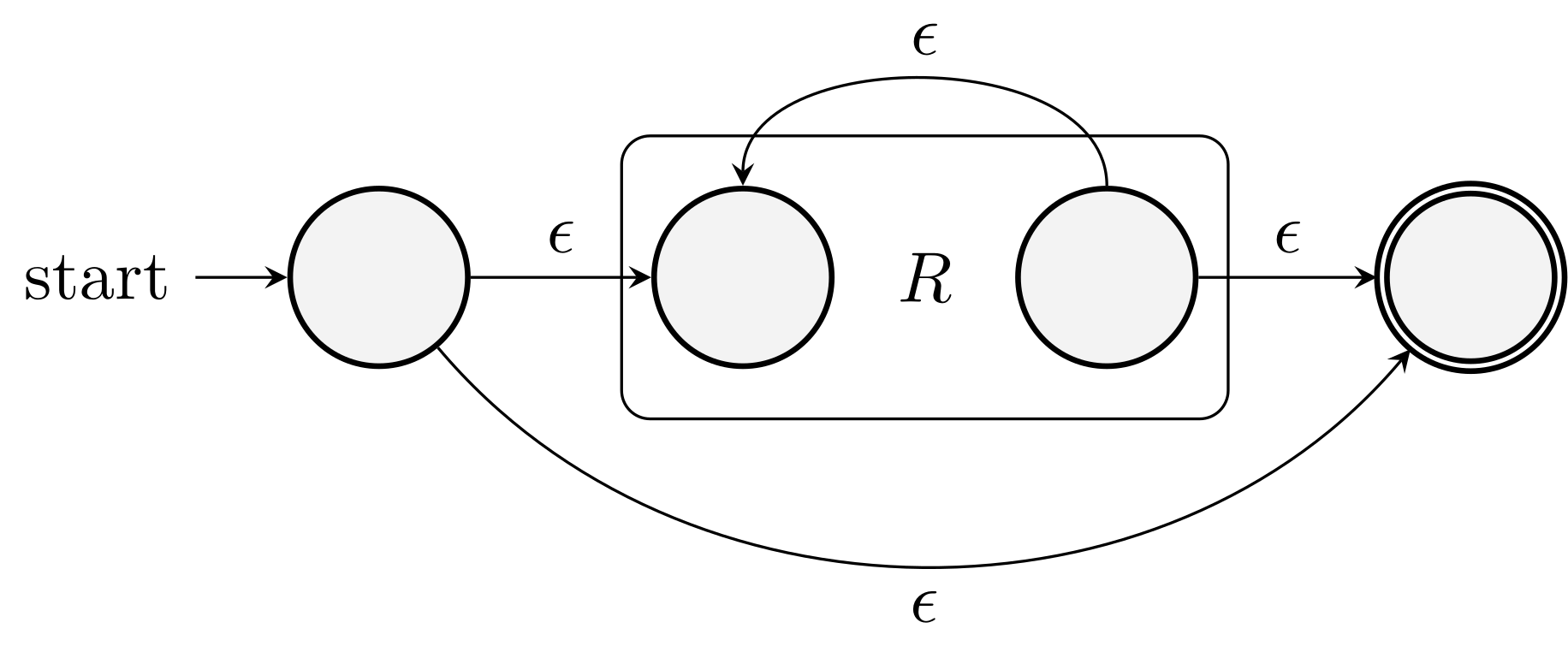

Induction: \(R+S\), \(RS\), \(R^*\).

See Figure 3.17 of the textbook for the full construction.

Example. Convert the regular expression \(1(0+1)^*\) to an \(\eps\)-NFA.

Algebraic Laws for RE

What is algebraic law

In mathematics

\(1 + 2 = 2 + 1\) vs \(x + y = y + x\)

Commutativity: The equality holds for all values of the variables \(x\) and \(y\)

Algebra: addition and multiplication

Algebraic laws for RE

Language \(L\) as the variables.

Union as the addition.

Concatenation as multiplication.

Associativity and commutativity

\((L+M)+N = L+(M+N)\)

\(L+M = M+L\)

\((LM)N = L(MN)\)

But not \(LM = ML\).

Identities and annihilators

\(\emptyset + L = L\), identity for addition

\(\eps L = L \eps = L\), identity for concatenation

\(\emptyset L = \emptyset\), annihilator for concatenation

Distributive laws

Let \(L, M, N\) be regular expressions. It holds that \(L(M+N) = LM + LN\).

How to prove it? By definition and set equality.

First, we prove \(L(M+N) \subseteq LM + LN\). For all \(w \in L(M+N)\), there is a partition \(w = w_1w_2\) such that \(w_1 \in L\) and \(w_2 \in M+N\). Case 1, \(w_2 \in M\), \(w \in LM\). Hence \(w \in LM + LN\). Case 2, \(w_2 \in N\), \(w \in LN\). Hence \(w \in LM + LN\).

Second, we prove \(LM + LN \subseteq L(M+N)\).

Idempotent law for union

\(L + L = L\)

Laws involving closures

\((L^*)^* = L^*\), any concatenation of concatenations is a concatenation

\(\emptyset^* = \eps\),

\(\eps^* = \eps\)

\(L^+ = LL^*\)

\(L^* = L^+ + \eps\)

Discovering laws for regular expressions

There is an infinite variety of laws about regular expressions that might be proposed!

Is there a general methodology for finding and proving algebraic laws for RE?

The truth of a law reduces to the equality of two specific languages

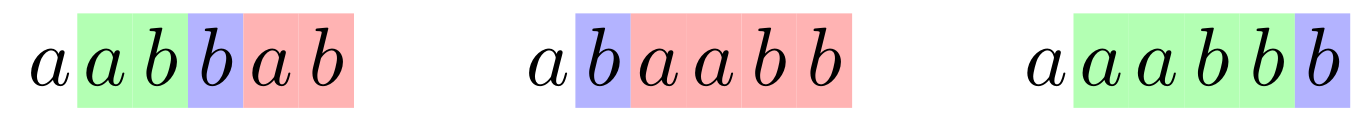

Example: \((L+M)^* = (L^*M^*)^*\)

We can specialize the RE operators to act on symbols, one symbol for each language.

- Think of variable \(L\) as a symbol \(a\), \(M\) as \(b\), we get \((a+b)^*\)

- Test if \((a+b)^* = (a^*b^*)^*\)

Main theorem

Theorem (3.13). (A lemma that defines \(L(E)\) alternatively) Let \(E\) be a RE with variables \(L_1, \ldots, L_m\). Let \(C\) be the corresponding concrete RE with symbols \(a_1, \ldots, a_m\). Then, for any instance languages \(S_1, \ldots, S_m\) of \(L_1, \ldots, L_m\), every string \(w\) in \(L(E)\) can be written \(w = w_1 \ldots w_k\), where each \(w_i\) is in one of the language \(S_{j_i}\), and the string \(a_{j_1} \ldots a_{j_k}\) is in the language \(L(C)\). Less formally, we can construct \(L(E)\) by starting with each string \(a_{j_1} \ldots a_{j_k}\) in \(L(C)\) and replacing \(a_{j_i}\) with a string in \(S_{j_i}\).

The intuitive meaning of the theorem is that, starting with a string in the concrete language, you can generate all and only the strings in \(L(E)\) by expanding each symbol into a string from the corresponding language associated with that symbol.

Structural induction on \(E\).

Basis. \(E\) is either \(\eps\), \(\emptyset\), or variable \(L\). If \(E\) is \(L\). \(L(E) = L\) and the concrete expression \(C\) is \(a\), a symbol corresponding to \(L\). Easy.

Induction. If \(E\) is the union, concatenation, or closure, we need to prove the claim.

Suppose \(E = F + G\). Let \(C\) and \(D\) be the concrete expressions of \(F\) and \(G\). Consider \(w \in L(E)\), then \(W\) is either in \(L(F)\) or \(L(G)\). Using induction hypothesis, \(w\) can be obtained by replacing symbols of strings in either \(L(C)\) or \(L(D)\). Hence, \(w\) can be generalized from a concrete string in \(L(C+D)\).

Similarly for \(E = FG\) and \(E= F^*\).

It is a simple method to test a law.

Theorem. \(L(E) = L(F)\) for all choices of languages \(L_1, L_2, \ldots, L_m\) in \(E\) and \(F\) if and only if \(L(C) = L(D)\) where \(C\) and \(D\) are the concrete RE's of \(E\) and \(F\).

The proof is simple and given in Theorem 3.14.

In the only if direction, use the singlet languages. In the other direction, use Theorem 3.13.

Example. \((L+M)^* = (L^*M^*)^*\) and \(L+ML \ne (L+M)L\).

Caveat

The method may become invalid if we add other operators (other than union, concatenation, closure)

Consider \(L \cap M \cap N = L \cap M\). It is obviously false, but \(\{a\} \cap \{b\} \cap \{c\} = \{a\} \cap \{b\}\).

Lecture 5: Pumping Lemma and Properties of Regular Languages

What we will discussion in the next two lectures:

- Proving that a language is not regular.

- Closure properties of RL.

- Finite automata equivalence checking.

- Minimize an automata.

Pumping Lemma

Not every language is regular.

We have proved this using the countability argument.

We will now see concrete examples.

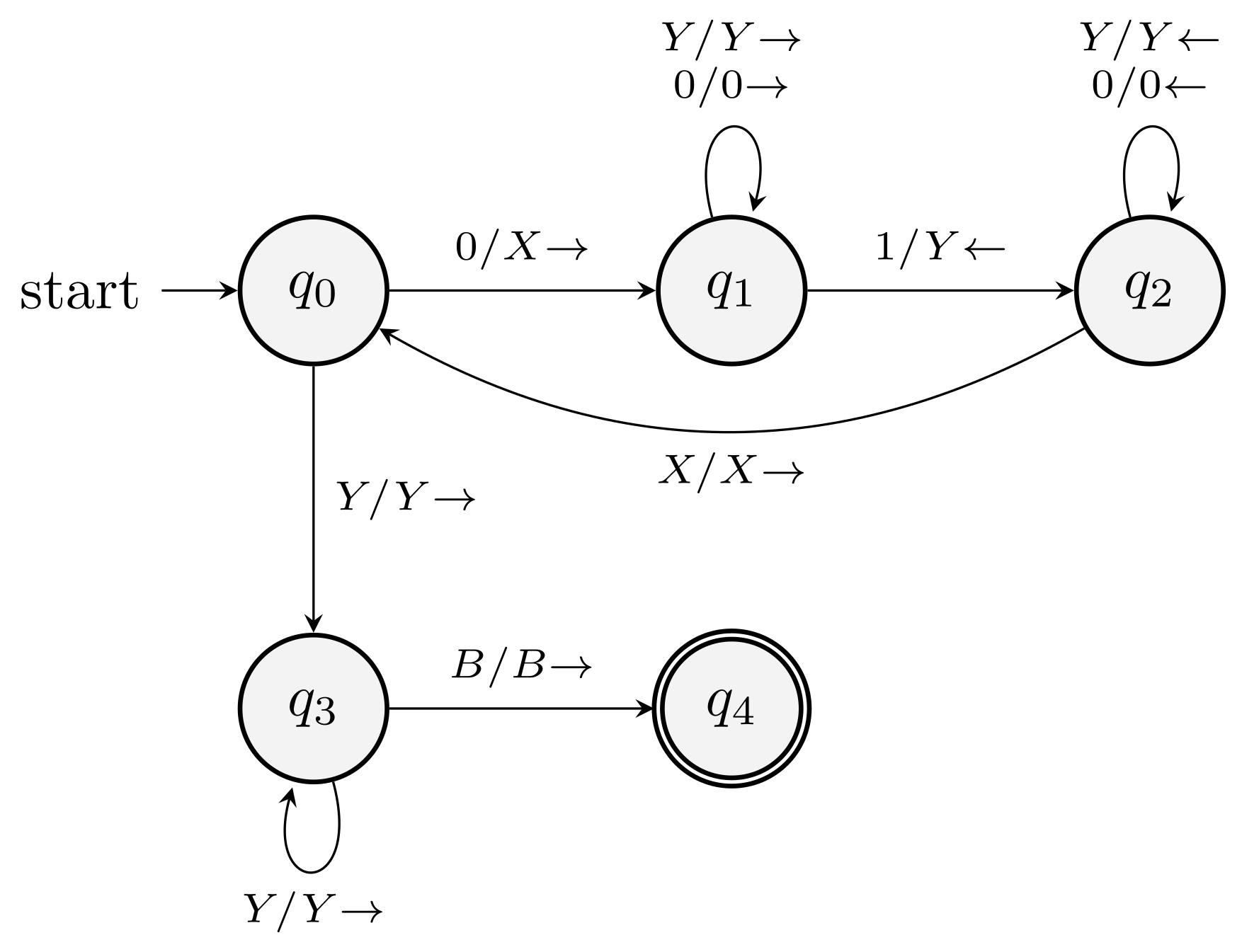

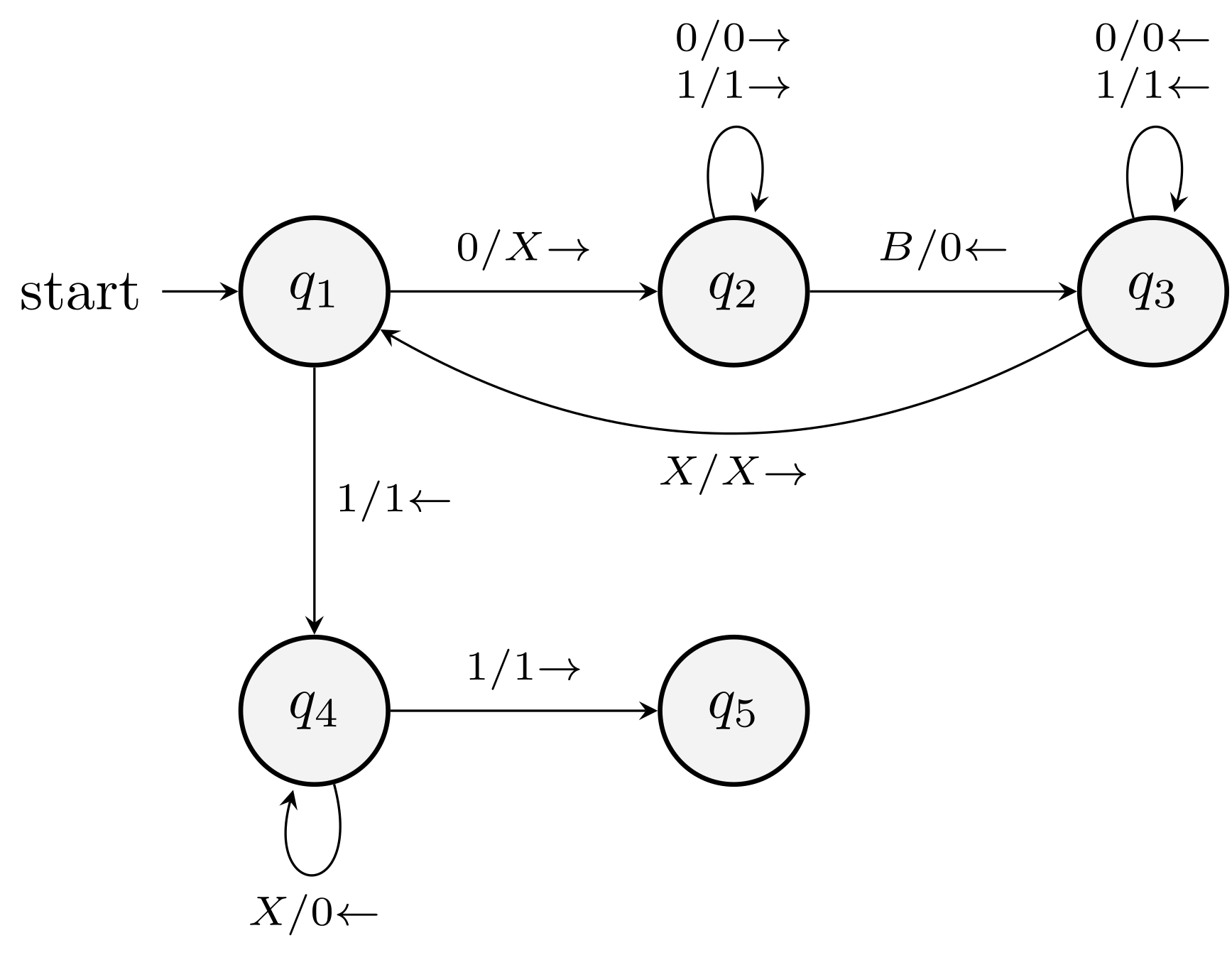

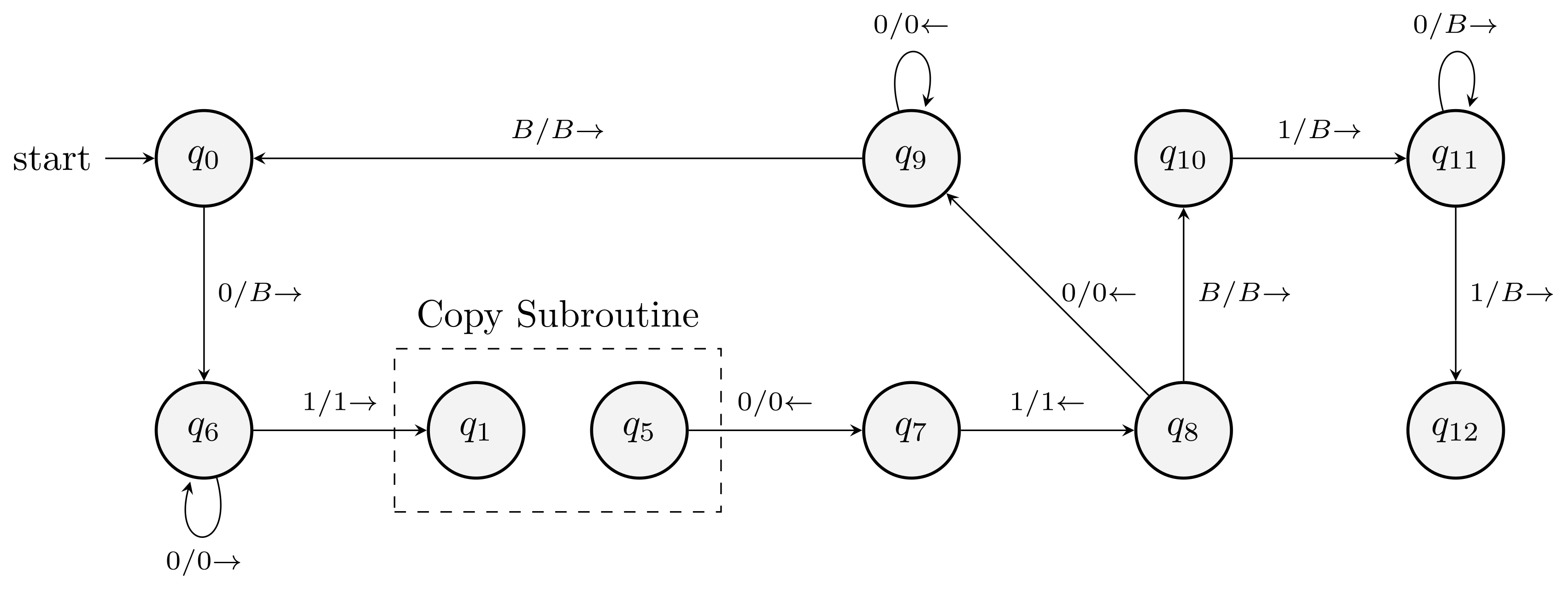

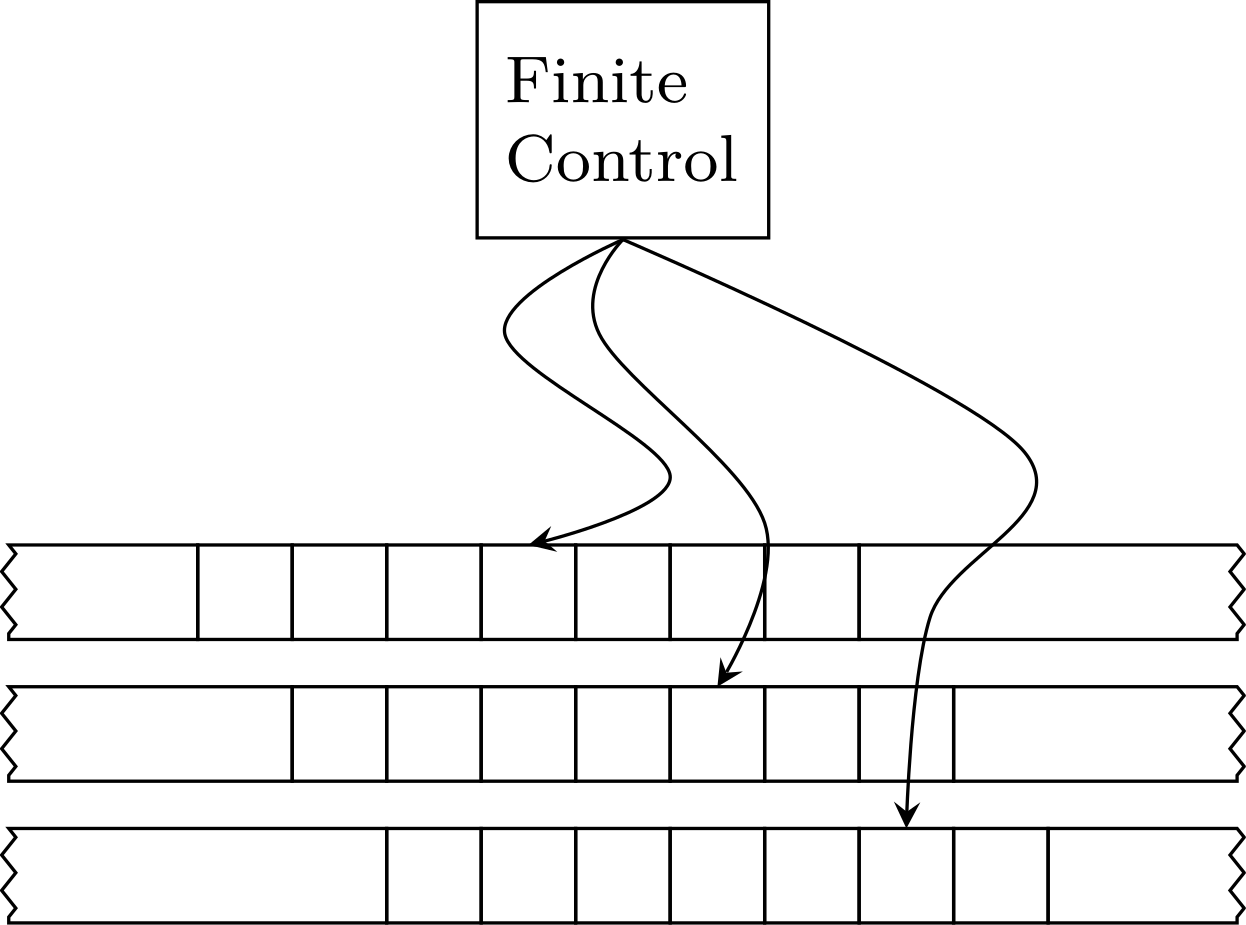

Example

\(L_{\text{EQ}} = \{0^n1^n \mid n \ge 1\}\) is not regular.

Note that it is not the concatenation of \(\{0^n \mid n \ge 1\}\) and \(\{1^n \mid n \ge 1\}\).

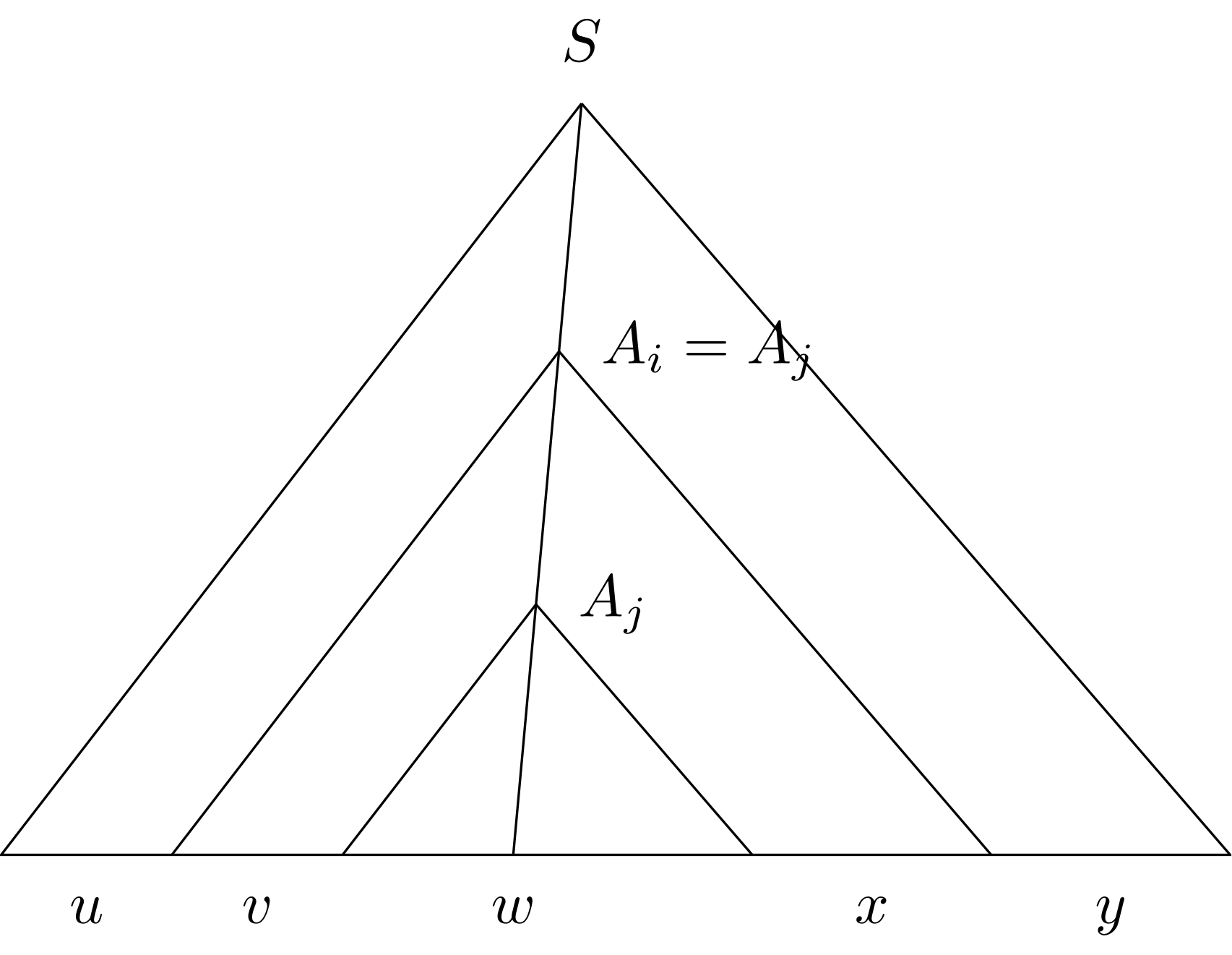

Pumping lemma

Let \(L\) be a regular language. Then there exists a constant \(n\) (which may depend on \(L\)) such that for every \(w\) in \(L\) such that \(\abs{w} \ge n\), we can break \(w\) into three strings \(x, y, z\) as \(w = xyz\), such that:

- \(y \ne \eps\).

- \(\abs{xy} \le n\).

- For all \(k \ge 0\), \(xy^kz\) is also in \(L\).

Proof

Use pigeonhole principle to argue that one has to visit a state again.

It's like a game between the 'for all' player and 'exist' player

For all \(L\), there is \(n\), for all \(w\) in \(L\), there is a partition such that for all \(k\), …

Examples

\(L_{\text{EQ}}\)

\(L_{\text{PAL}} = \{ w \mid w = w^R\}\)

\(L_{\text{PRIME}} = \{1^p \mid p \text{ is prime}\}\)

Assume to the contrary that \(L_{\text{PRIME}}\) is a regular language.

By the pumping lemma, there is a constant \(n\), such that for all prime \(p \ge n\), we can partition \(1^p\) into three parts \(x, y, z\) with \(y \ne \eps\), such that \(xy^kz \in L_{\text{PRIME}}\). That is, \(p + (k-1) \abs{y}\) is prime for all \(k\). Choose \(k = p+1\), we have a contradiction. So \(L_{\text{PRIME}}\) cannot be regular.

\(L_{\text{SQUARE}} = \{1^{m^2} \mid m \in \mathbb{N} \}\)

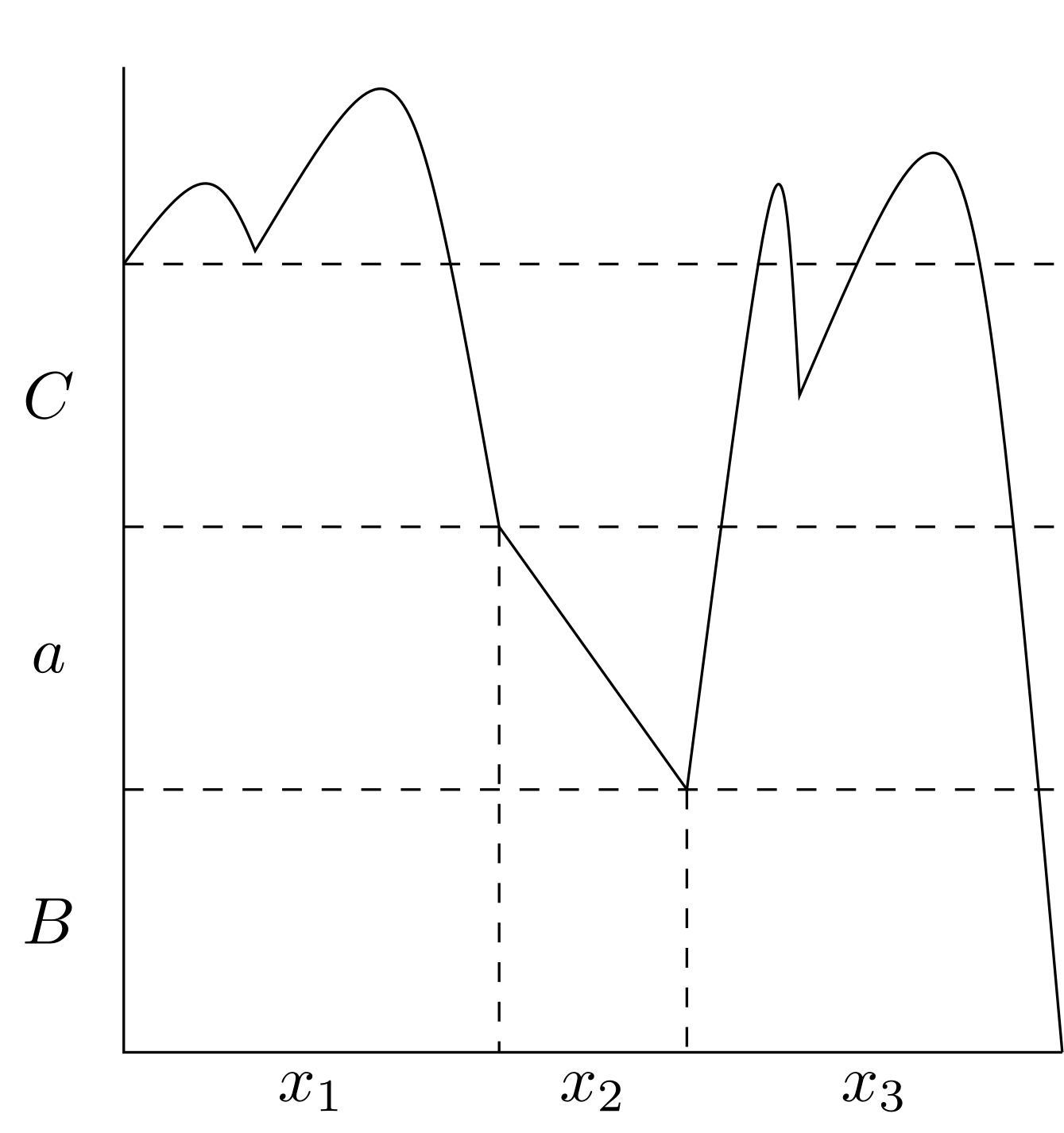

Myhill–Nerode theorem

It provides an if and only if condition for a language to be regular.

EXTRA: Check it out yourself if you are interested. Not required for this course.

Closure Properties

Closure properties

The result of certain operation on regular languages is still regular

- Union

- Closure (star)

- Concatenation

- Intersection

- Complement

- Difference

- Reversal

- Homomorphism

- Inverse homomorphism

Union, intersection, complement

Union

There are \(L=L(R)\), \(M=L(S)\) for RE \(R\) and \(S\) respectively. \(L \cup M = L(R+S)\) by the definition of \(+\).

Complement

Let \(A = (Q, \Sigma, \delta, q_0, F)\) be the DFA for the language.

Complement the accepting states. That is, consider \(A' = (Q, \Sigma, \delta, q_0, Q \setminus F)\).

Closure under intersection!

Idea: Finite memory vs states

Suppose we have DFA's \(A\) and \(B\) for languages \(L\) and \(M\) respectively.

How to design a DFA \(C\) for \(L \cap M\)?

It is known as product construction.

Reversal

The reversal of a string \(w=a_1 \cdots a_n\) is the string \(a_n \cdots a_1\), denoted as \(w^R\).

Define \(L^R = \{w^R \mid w \in L\}\).

If \(L\) is regular, so is \(L^R\).

It can be proved easily via either the automata picture or the RE picture.

See extra notes for how to develop a formal proof from scratch using the reversal as an example.

Lecture 6: Closure, Decision, Equivalence, and Minimization

Closure Properties (cont.)

- Union

- Closure (star)

- Concatenation

- Intersection

- Complement

- Difference

- Reversal

- Homomorphism

- Inverse homomorphism

Homomorphism

A string homomorphism is a function on strings that works by substituting a particular string for each symbol.

Example: \(h(0)=000\), \(h(1)=111\), and \(h(w)=h(a_1) \cdots h(a_n)\).

\(h: \Sigma \rightarrow \Gamma^*\)

Proof. Induction using RE in the textbook.

It is also easy to prove using automata.

Inverse homomorphism

Definition

\(h\) induces a map \(\Sigma^* \rightarrow \Gamma^*\).

\(h^{-1}(L)\) is the set of preimages whose homomorphism is in \(L\).

Example (4.15). \(L\) is \((00+1)^*\), \(h(a) = 01\), \(h(b)=10\). Show that \(h^{-1}(L)\) is \((ba)^*\). Equivalently, \(h(w) \in L\) if and only if \(w\) is of the form \(baba\cdots ba\).

(If) Easy.

(Only-if) Consider the four cases if \(w\) starts with \(a\), ends with \(b\), has \(aa\) as a substring, or has \(bb\) as a substring. These will lead to a \(0,1\) string with a single \(0\) and should be excluded.

So the string has to start with \(b\) and end with \(a\) and is alternating between \(a\) and \(b\).

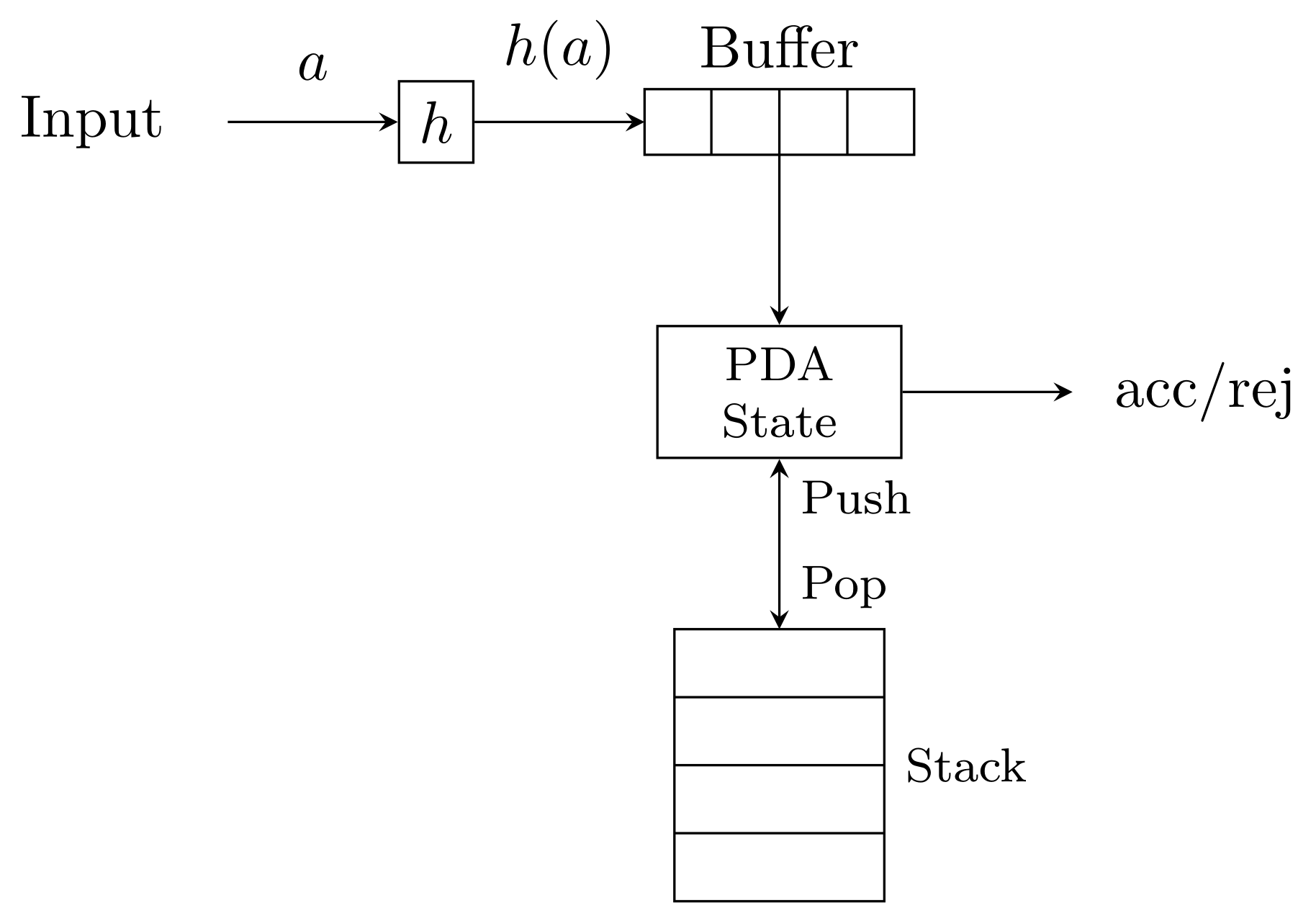

Inverse homomorphism has the closure property

Theorem. If \(L\) is RE, so is \(h^{-1}(L)\).

Not hard—Fig 4.6 of the textbook.

Let \(A = (Q, T, \delta, q_0, F)\) be the DFA for language \(L\). Define \(B = (Q, \Sigma, \gamma, q_0, F)\) where \(\gamma(q, a) = \hat{\delta}(q, h(a))\).

Prove by induction on \(\abs{w}\) that \(\hat{\gamma}(q, w) = \hat{\delta}(q, h(w))\).

Other Closure Properties

Prefix, suffix, substring!

\[\begin{equation*} \text{Prefix}(L) = \{ u \mid \text{ There is } v \in \Sigma^* \text{ such that } uv \in L\}. \end{equation*}\]

One of your homework problems

NOTE (Mark any states that can reach an accepting state as an accepting state).

Example

Prove that \(\{a^i b^j c^k \mid i,j,k \ge 0, j=k \text{ if } i=1\}\) is not regular.

The pumping lemma won't work!

Intersect with \(\{a b^j c^k\}\),

Consider homomorphism \(h(a) = \eps, h(b) = 0, h(c) = 1\).

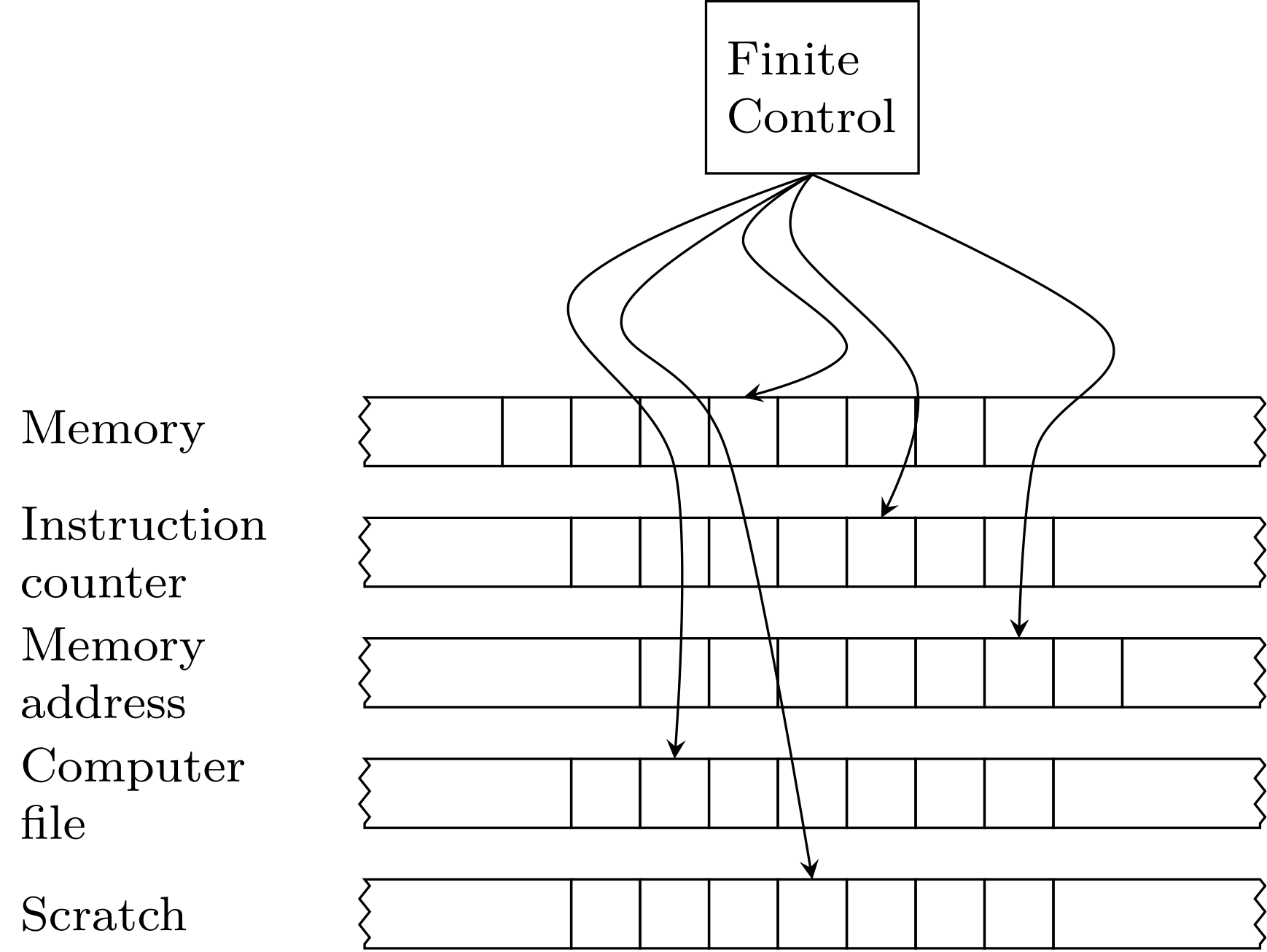

Decision Properties

Emptiness, membership, equivalence

Conversion among different representations

\(\eps\)-NFA's to DFA's

Time complexity \(O(n^3 2^n)\) where \(n^3\) comes from the computation for reachable states for all \(n\) states. (Assume the size of the alphabet is a constant)

Often, the complexity is much smaller.

Use lazy evaluation of subsets

\(O(n^3 s)\) where \(s\) is the number of states in the resulting DFA.

Automata to RE

Recall (worst-case) complexity is high \(O(n^3 4^n)\).

Both Kleene construction and the state elimination method have the above complexity.

Do not convert NFA to DFA and then to RE, as it could be doubly exponential!

Emptiness of an RL

Easy to do if we are given a RE explicitly

If given as an FA, emptiness reduces to graph reachability and has time complexity \(O(n^2)\) where \(n\) is the number of states.

Membership

Testing membership is easy if we are given a DFA. By running the DFA, we can solve it in time linear in \(\abs{w}\).

Testing membership for NFA, \(\eps\)-NFA, and RE

Time complexity: \(O(\abs{w} n^2)\).

If we are given an NFA, it is more efficient to simulate on an NFA, maintaining the set of states directly.

If we are given an \(\eps\)-NFA, compute successor states and the \(\eps\)-closure.

If we are given an RE of size \(n\), we can convert it to an \(\eps\)-NFA of size at most \(2n\).

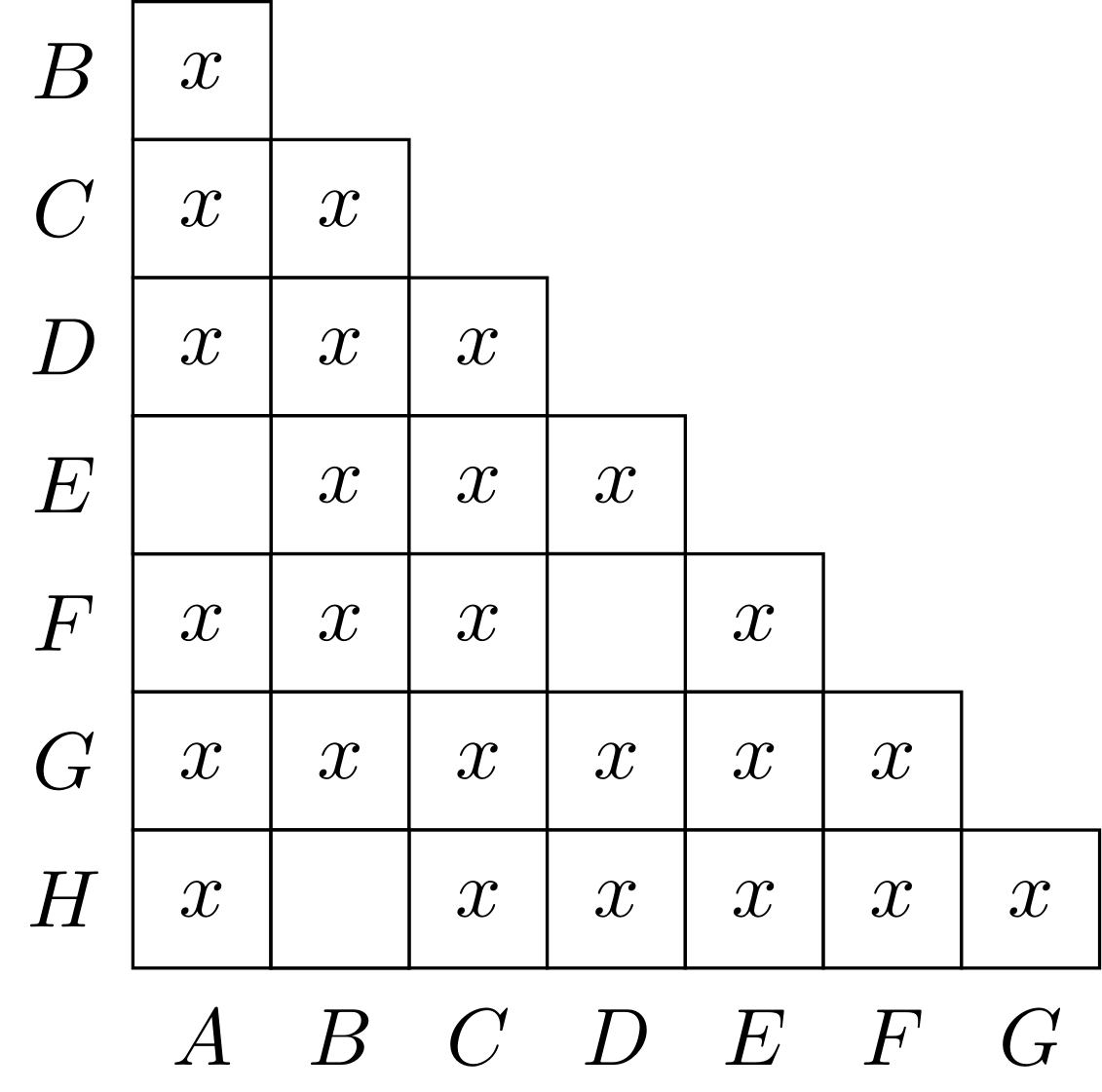

Equivalence and Minimization

State equivalence

Test if two states of a single DFA are equivalent.

\(p, q\) are equivalent if \(\hat{\delta}(p,w)\) is an accept state if and only if \(\hat{\delta}(q,w)\) is for all \(w\).

If two states are not equivalent, we say they are distinguishable.

To find equivalent states, we do our best to find pairs of states that are distinguishable.

States we cannot find distinguishable are equivalent.

Table-filling algorithm: Recursive discovery of distinguishable pairs

Basis: If \(p\) is accepting and \(q\) is non-accepting, they are distinguishable.

Induction: Let \(p\) and \(q\) be states such that for some symbol \(a\), \(\delta(p,a)\) and \(\delta(q,a)\) are a pair of known different states, then they are distinguishable.

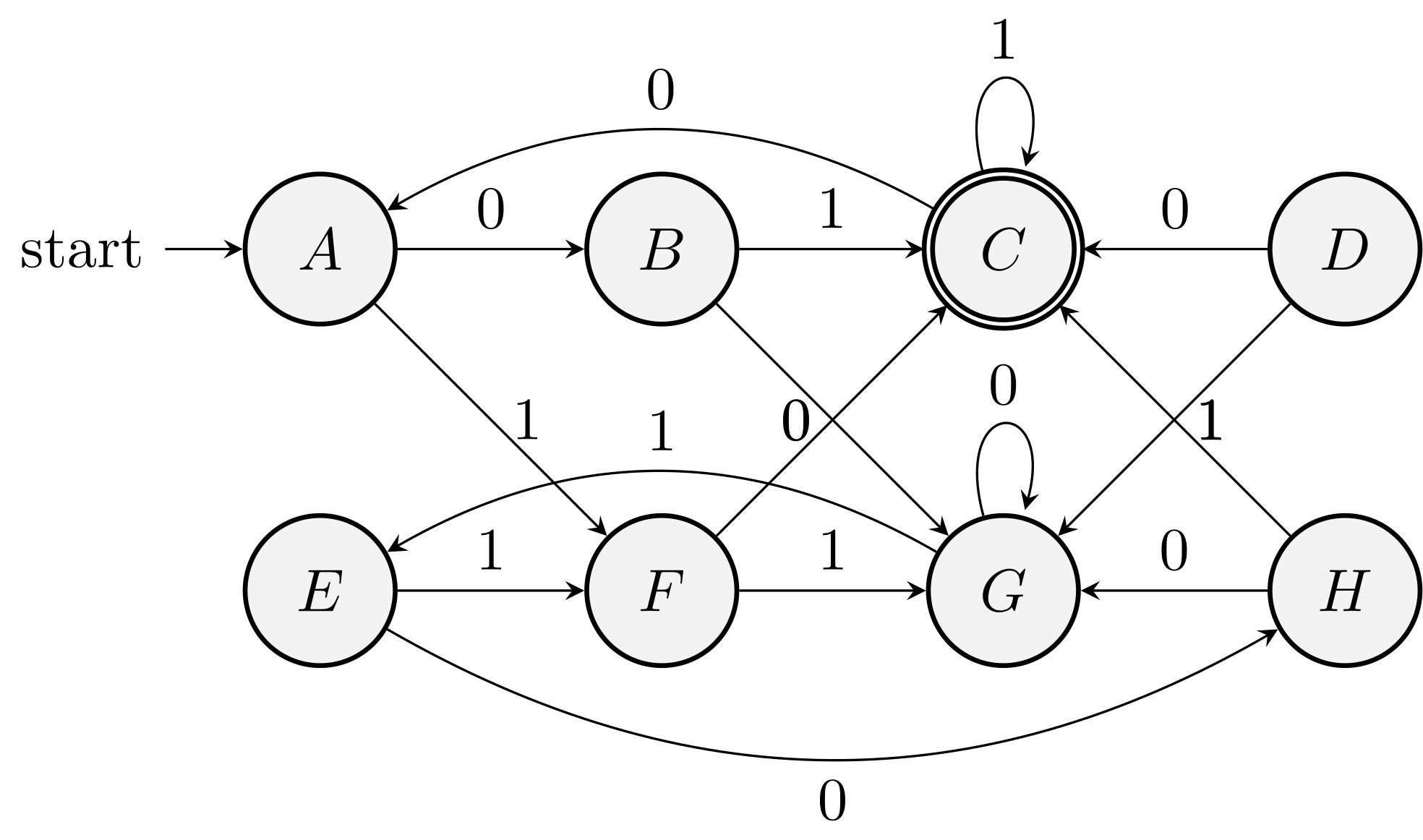

Example (4.18 of the textbook)

Main theorem

Theorem. If two states are not distinguishable by the table-filling algorithm, then they are equivalent.

Assume the theorem is false. That is, there are \(p\), \(q\), distinguishable, but the algorithm does not detect that. Call them bad pairs.

Let \(w\) be one of the shortest strings that distinguish bad pairs. Let the bad pair be \(p\), \(q\).

First, \(w\) cannot be \(\eps\) by the basis of the algorithm. Write \(w = a w'\) and consider \(p' = \delta(p, a)\) and \(q' = \delta(q, a)\).

- If \(p'\) and \(q'\) form a bad pair (distinguishable but not detected). \(w'\) will be a shorter (than w) string that distinguishes a bad pair. Contradiction!

- If \(p'\) and \(q'\) are distinguishable and detected by the algorithm, the induction part of the algorithm will find \(p,q\) distinguishable, and it's contradiction with the fact that \(p,q\) form a bad pair.

- If \(p'\) and \(q'\) are equivalent, \(w\) cannot distinguish \(p\) and \(q\). Contradiction.

As in all possible cases we have a contradiction, our initial assumption is false and the theorem is proved.

There are two important applications of this theorem.

Test equivalence

Put two DFAs together and apply the table-filling algorithm to test if the two start states are equivalent.

Complexity: Easy to show the \(O(n^4)\) bound. We have \(n^2\) pairs, and each will take at most \(O(n^2)\) time.

A careful choice of data structure and analysis shows a \(O(n^2)\) bound. For each pair of states, maintain a list of states that depends on it.

Minimization

- Remove disconnected parts

- Partition the states by equivalence.

Theorem (transitivity). If \(p, q\) are equivalent, \(q, r\) are equivalent, then \(p, r\) are equivalent.

Easy to show. Proof by contradiction.

Use the partitions as states.

It is an equivalence relation (reflexivity, symmetry, transitivity).

Why is it minimal

Let \(M\) be the FA we get from the above. \(N\) is a FA with fewer states accepting the same language.

The starting state of \(M\) and \(N\) are equivalent.

For any state \(p\) in \(M\), there is a \(q\) in \(N\) that are equivalent to \(p\). (Consider a string \(w\) that brings the automaton \(M\) to state \(p\))

Two states in \(M\) are equivalent, a contradiction.

Lecture 7: Context-Free Grammars and Languages

A larger class of languages (CFL) is defined by a natural, recursive notation called CFG.

It is central to compiler technology.

They turned the implementation of parsers from a time-consuming task to a routine job that can be done in an afternoon.

Context-free Grammars (CFG's)

Example

Consider \(L_\text{pal}\) which is the set of binary strings that are palindromes.

Palindrome is not regular.

How to define palindromes?

Basis: \(\eps, 0, 1\) are palindromes.

Induction: If \(w\) is a palindrome, so are \(0w0\) and \(1w1\).

A CFG is a formal notation for expressing such recursive definitions of languages.

A grammar consists of one or more variables that represent languages. In this example, we need only one variable, \(P\).

- \(P \rightarrow \eps\)

- \(P \rightarrow 0\)

- \(P \rightarrow 1\)

- \(P \rightarrow 0P0\)

- \(P \rightarrow 1P1\)

Formal definition

There are four components in a grammatical description of a language:

A finite set of variables.

A finite set of symbols that form the strings of language being defined.

terminals or terminal symbols

A finite set of productions or rules that represent the recursive definition of the language.

One of the variables represents the language being defined. It is called the start symbol.

Each rule consists of:

a. A variable that is being (partially) defined by the production. Often called the head.

b. A production symbol \(\rightarrow\).

c. A string of zero or more terminals and variables. It is called the body.

A CFG is a \(G=(V,T,P,S)\).

Example

\(G_\text{pal} = (\{P\}, \{0,1\}, A, P)\)

Example II

A CFG that represents (a simplification of) expressions in a typical programming language.

\(+\), \(*\), Identifier consists of \(a, b, 0, 1\) only

- \(E \rightarrow I\)

- \(E \rightarrow E + E\)

- \(E \rightarrow E * E\)

- \(E \rightarrow (E)\)

- \(I \rightarrow a\)

- \(I \rightarrow b\)

- \(I \rightarrow Ia \,|\, Ib \,|\, I0 \,|\, I1\)

\(G = (\{E, I\}, T, P, E)\)

\(T\) is \(\{+, *, (, ), a, b, 0, 1\}\)

Derivations of CFG

There are two ways to infer that a particular string is in the language: body to head (recursive inference) and head to body (derivation).

Derivation \(\Rightarrow\)

\(\alpha A \beta\), \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are strings in \((V \cup T)^*\) and \(A\) is in \(V\). Let \(A \rightarrow \gamma\) be a rule. Then we say \(\alpha A \beta \Rightarrow \alpha \gamma \beta\).

One derivation step replaces any variable anywhere in the string to the body of one of its production rule.

\(\Rightarrow^*\) zero or more steps of derivation.

Example:

\[\begin{equation*} \begin{split} E & \Rightarrow E * E \Rightarrow I * E \Rightarrow a * E \\ & \Rightarrow a * (E) \Rightarrow a * (E + E) \Rightarrow a * (I + E) \\ & \Rightarrow a * (a + E) \Rightarrow a * (a + I) \Rightarrow a * (a + I0) \\ & \Rightarrow a * (a + b0) \end{split} \end{equation*}\]

Recursive inference vs. derivation.

Leftmost and rightmost derivations

To restrict the number of choices we have in deriving a string.

In each step of leftmost derivations, we replace the leftmost variable in derivations.

\(\Rightarrow_{\text{lm}}\)

\(E \Rightarrow_{\text{lm}} a * (a + b0)\)

\(A \Rightarrow^* w\) if and only if \(A \Rightarrow^*_{\text{lm}} w\)

\(A \Rightarrow^* w\) if and only if \(A \Rightarrow^*_{\text{rm}} w\)

The language of a grammar

- \(L(G) = \{w \in T^* \mid S \Rightarrow^* w\}\)

Theorem. \(L(G_\text{pal})\) is the set of palindromes over \(\{0,1\}\).

What to prove?

(If) \(w\) is a palindrome implies that \(P \Rightarrow^* w\). Use an induction on the length of \(w\).

(Only-if) For all \(w\) such that \(P \Rightarrow^* w\), we conclude that \(w\) is a palindrome. Use an induction on the number of steps in the derivation.

Examples

Construct a CFG for \(\{a^n b^m c^m d^n \mid m, n \ge 1\}\).

Inner part is what we are familiar with.

\(D \rightarrow b D c \,|\, bc\).

Outer part has pairs of \(a\) and \(d\).

\(C \rightarrow a C d \,|\, D\).

Need at least one pair of \(a, d\).

\(S \rightarrow a C d\).

The final answer is therefore \[\begin{align*} S & \rightarrow aCd\\ C & \rightarrow aCd \,|\, D\\ D & \rightarrow bDc \,|\, bc. \end{align*}\]

Construct CFG for \(\{a^m b^n \mid m,n\ge 0, m \ne n\}\).

Use \(A \rightarrow aA \,|\, aAb \,|\, \eps\) to get strings with the condition \(m \ge n\).

Use \(S \rightarrow aA\) to get \(m > n\).

Handle the case of \(m < n\) similarly.

The final solution is \[\begin{align*} S & \rightarrow aA \,|\, Bb\\ A & \rightarrow aA \,|\, aAb \,|\, \eps\\ B & \rightarrow Bb \,|\, aBb \,|\, \eps. \end{align*}\]

Construct CFG for \(\{w \mid w \in \{a,b\}^*, \text{occor}(a, w) = \text{occur}(b, w)\}\).

This is hard as \(a, b\) can be in any order.

Say the string starts with \(a\), we know the tail has one more \(b\).

Color the first \(b\) blue where we have one more \(b\) in the tail and partition the tail into three parts.

It is now easy to write down the rules: \[\begin{equation*} S \rightarrow aSbS \,|\, bSaS \,|\, \eps. \end{equation*}\]

It is a homework problem to prove this construction works.

Let \(G\) be a context-free grammar whose terminal set is \(\{a,b\}\) and starting symbol is \(S\). The production rules are

- \(S \rightarrow \eps \,|\, aB \,|\, bA\),

- \(A \rightarrow a \,|\, aS \,|\, bAA\),

- \(B \rightarrow b \,|\, bS \,|\, aBB\).

Prove that \(L(G) = \{w \mid w \in \{a,b\}^*, \text{occor}(a, w) = \text{occur}(b, w)\}\) too.

Idea: Use mutual induction to prove the following:

a. \(S \Rightarrow^* w\) if and only if \(\text{occur}(a, w) = \text{occur}(b, w)\);

b. \(A \Rightarrow^* w\) if and only if \(\text{occur}(a, w) = \text{occur}(b, w) + 1\);

c. \(B \Rightarrow^* w\) if and only if \(\text{occur}(b, w) = \text{occur}(a, w) + 1\).

Chomsky hierarchy

- Type-0

- Language: Recursive enumerable

- Automata: Turing machine

- Production: \(\gamma \rightarrow \alpha\), \(\gamma\) contains a variable

- Type-1

- Context-sensitive

- Linear-bounded automata

- \(\alpha A \beta \rightarrow \alpha \gamma \beta\) with nonempty \(\gamma\)

- Type-2

- Context-free

- Pushdown automata

- \(A \rightarrow \alpha\)

- Type-3

- Regular

- Finite state automata

- \(A \rightarrow a, A \rightarrow a B\)

Parse tree

A tree representation for derivations.

It is the data structure that represents source programs.

Ambiguity

Constructing parse trees

Given a grammar \(G = (V, T, P, S)\).

The parse trees for \(G\) are trees with the following conditions:

- Each interior node is labeled by a variable in \(V\).

- Each leaf is labeled by either a variable, a terminal or \(\eps\). However, if the leaf is labeled \(\eps\), it must be the only child of its parent.

- If an interior node is labeled \(A\), and its children are labeled \(X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_k\), then \(A \rightarrow X_1 \cdots X_k\) is a production of \(G\).

Example

Parse tree for the derivation of \(I + E\) from \(E\).

The yield of a parse tree

The string of leave contents from left to right.

The yield is what can be derived from the root.

An important case:

- The yield is a terminal string.

- The root is labeled by the start symbol.

Inference, derivations, and parse trees

See Section 5.2 of the textbook for details.

The following are equivalent

- The recursive inference procedure determines that terminal string \(w\) is in the language of variable \(A\).

- \(A \Rightarrow^* w\).

- \(A \Rightarrow^*_{\text{lm}} w\).

- \(A \Rightarrow^*_{\text{rm}} w\).

- There is a parse tree with root \(A\) and yield \(w\).

Proof technique: equivalence.

\(5 \rightarrow 3 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow 1 \rightarrow 5\)

\(5 \rightarrow 4 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow 1 \rightarrow 5\)

\(1\rightarrow 5\): Induction on the number of steps used to infer that \(w\) is in the language of \(A\).

Basis: One step. \(A\rightarrow w\). Construct the parse tree directly.

Induction. Suppose \(w\) is inferred after \(n+1\) steps and suppose that for all \(x\) and \(B\) such that the membership of \(x\) in \(B\) was inferred using \(n\) or fewer steps satisfies the theorem. The last step uses a rule \(A\rightarrow X_1 \cdots X_k\). We can break \(w\) into \(w_1 \cdots w_k\) such that

- If \(X_i\) is a terminal, …

- If \(X_i\) is a variable, …

\(5\rightarrow 3\): Let \(G=(V,T,P,S)\) be a CFG, and suppose there is a parse tree with root variable \(A\) and yield \(w \in T^*\). Then there is a leftmost derivation \(A \Rightarrow^*_{\text{lm}} w\) in grammar \(G\).

Induction on the depth of the parse tree. Induction in induction.

\[\begin{equation*} A \Rightarrow^*_{\text{lm}} w_1 w_2 \cdots w_i X_{i+1} \cdots X_k \end{equation*}\]

\(3\rightarrow 2\): trivial.

\(2\rightarrow 1\): Induction on the length of the derivation \(A \Rightarrow^* w\). \(A \Rightarrow X_1 \cdots X_k \Rightarrow^* w\). Then (by proof of induction), we can write \(w = w_1 \cdots w_k\) such that …

Applications of CFG

It is initially discovered by N. Chomsky as a way to describe natural language.

A brief introduction on its uses:

For programming language, CFG provides a mechanical way of turning language descriptions to parse trees. It is one of the first ways in which theoretical ideas in CS found their way into practice.

XML, DTD in XML is essentially a CFG.

Example: html documents (formatting of text).

<html><head></head><body></body></html>

It becomes possible to define and parse the structured documents formally.

Ambiguity

The assumption: a grammar uniquely determines a structure for each string in its language.

That is not always the case.

Sometimes, we can redesign the grammar. Sometimes, we cannot! (inherently ambiguous)

\(E + E * E\) has two derivations from \(E\). The difference is significant.

But sometimes, there are different derivations without significant consequences:

- \(E \Rightarrow E + E \Rightarrow I + E \Rightarrow a + E \Rightarrow a + I \Rightarrow a + b\)

- \(E \Rightarrow E + E \Rightarrow E + I \Rightarrow I + I \Rightarrow I + b \Rightarrow a + b\)

Ambiguity is caused not by the multiplicity of derivations but by the existence of two or more parse trees.

Definition. A CFG is ambiguous if there is a \(w \in T^*\), which has two different parse trees, each with root label \(S\) and yield \(w\). Otherwise, the grammar is unambiguous.

Removing ambiguity

There is no algorithm to tell if a grammar is ambiguous or not (Theorem 9.20)!

There are CFLs that have nothing but ambiguous grammars!

In most practical applications, it is possible to remove ambiguity.

Two causes of ambiguity:

- The precedence of operators is not respected.

- A sequence of identical operators can group either from the left or right.

In the expression example (Example II):

- A factor is an expression that cannot be broken apart by any adjacent operator, either \(+\) or \(*\). In this case, identifier and \(()\).

- A term is an expression that cannot be broken apart by \(+\).

- An expression is any possible expression.

\(I \rightarrow a \,|\, b \,|\, Ia \,|\, Ib \,|\, I0 \,|\, I1\)

\(F \rightarrow I \,|\, (E)\)

\(T \rightarrow F \,|\, T * F\)

\(E \rightarrow T \,|\, E + T\)

It is unambiguous and generates the same language.

Key idea: Create different variables, each representing different binding strengths.

Another example

Dangling else problem: \(S \rightarrow \eps \,|\, iS \,|\, iSeS\) is ambiguous

\(iie\) does not tell us which if statement the else statement referees to.

When the first \(S\) in \(iSeS\) has less \(e\) than \(i\), there will be ambiguity as we don't know which \(i\) the \(e\) is paired with.

The following grammar matches the else with the closest if statement

- \(S \rightarrow \eps \,|\, iS \,|\, iMeS\),

- \(M \rightarrow \eps \,|\, iMeM\).

Derivations are not necessarily unique, even if the grammar is unambiguous. Yet leftmost/rightmost derivations are.

For grammar \(G=(V,T,P,S)\), and string \(w \in T^*\), \(w\) has two distinct parse trees if and only if \(w\) has two distinct leftmost derivations from \(S\).

Proof. Easy. Find the first place where the difference happens.

Example of an inherently ambiguous language

Consider language \(L = \{a^nb^nc^md^m \,|\, m,n\ge 1\} \cup \{a^nb^mc^md^n \,|\, m,n\ge 1\}\) and a CFG for \(L\) \[\begin{align*} S & \rightarrow AB \,|\, C\\ A & \rightarrow aAb \,|\, ab\\ B & \rightarrow cBd \,|\, cd\\ C & \rightarrow aCd \,|\, aDd\\ D & \rightarrow bDc \,|\, bc. \end{align*}\]

We can generate \(a^nb^nc^nd^n\) in two ways. All CFG for this language are ambiguous (see Section 5.4.4 of the textbook).

Lecture 8: Pushdown Automata

Outline

CFLs have a type of automaton that defines them.

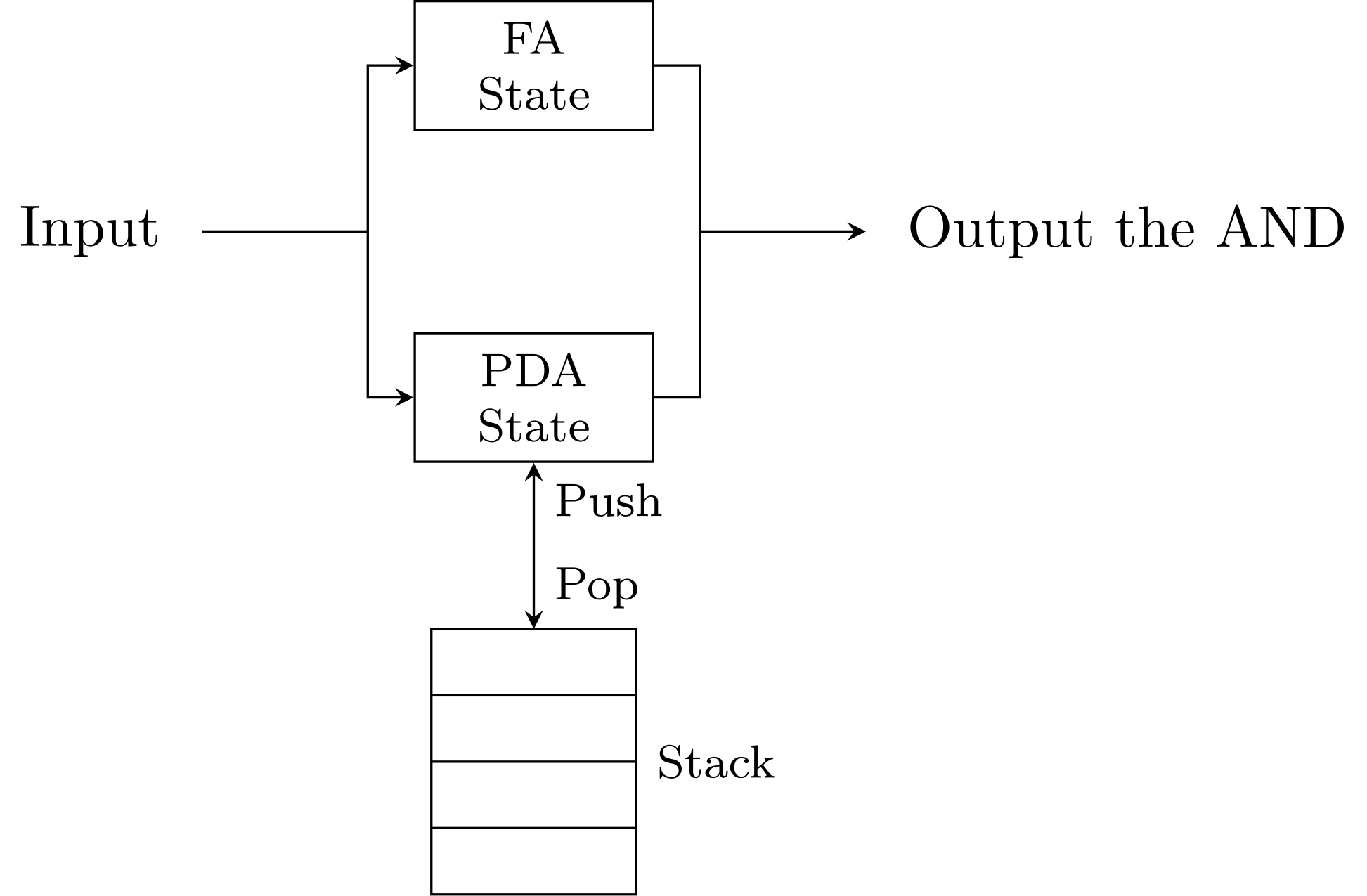

Pushdown automata: \(\eps\)-NFA + a stack.

We will consider two types of PDAs, one that accepts by entering an accepting state and one that accepts by emptying its stack.

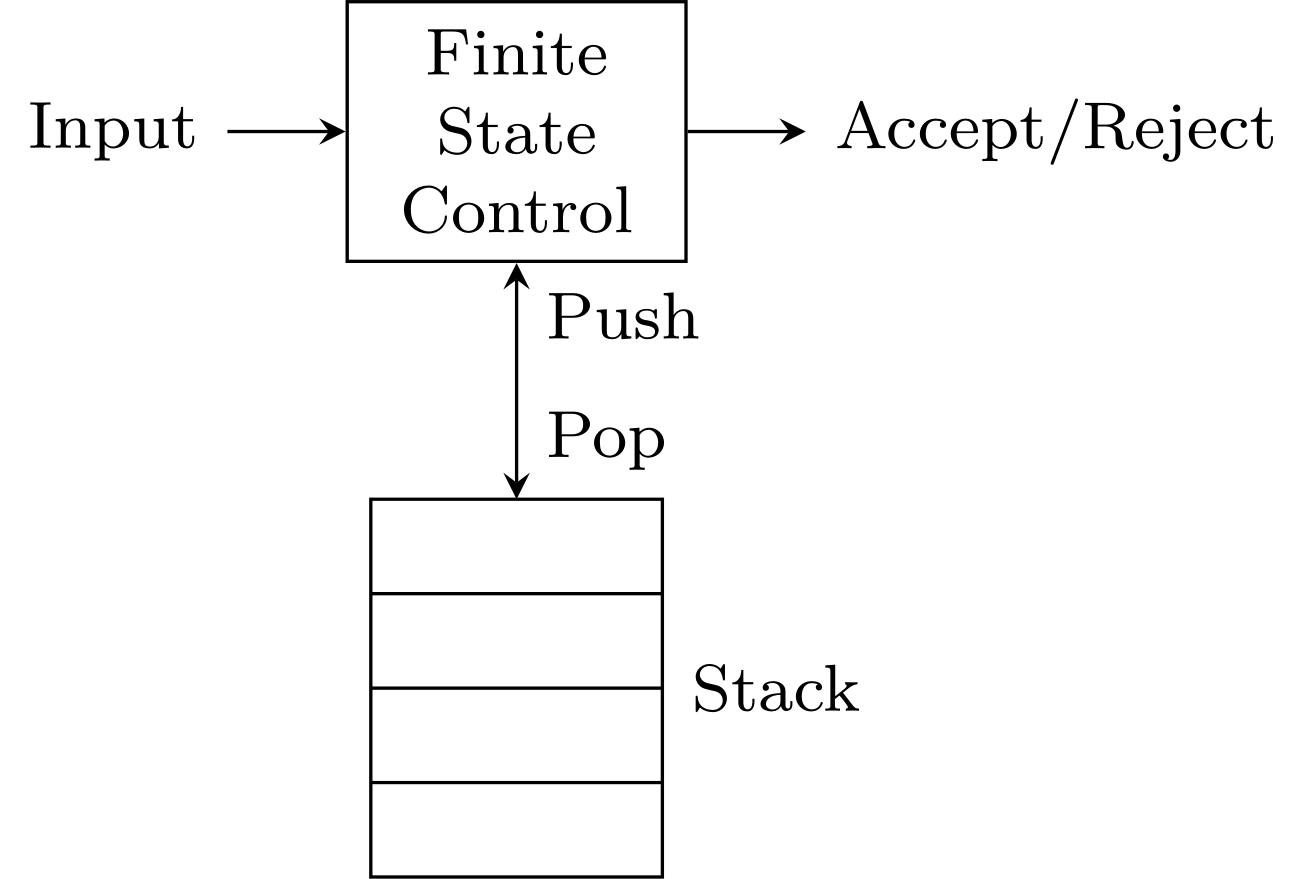

Definition of a PDA

PDAs can "remember" an infinite amount of information in a restricted manner. (FILO, stack)

Indeed, there are languages that can be recognized by some computer programs (TMs) but not by PDAs.

For example, \(\{0^n1^n2^n \mid n \ge 1\}\) is not a CFL (proved later).

A finite state control, taking inputs and outputs accept/reject while accessing a stack.

Transition of a PDA

In one transition the PDA:

- Consumes an input symbol.

- Goes to a new state.

- Replaces the symbol at the top of the stack by any string. The string could be \(\eps\), where the action corresponds to pop. It could be the same symbol at the top, meaning no change to the stack.

Example of a PDA

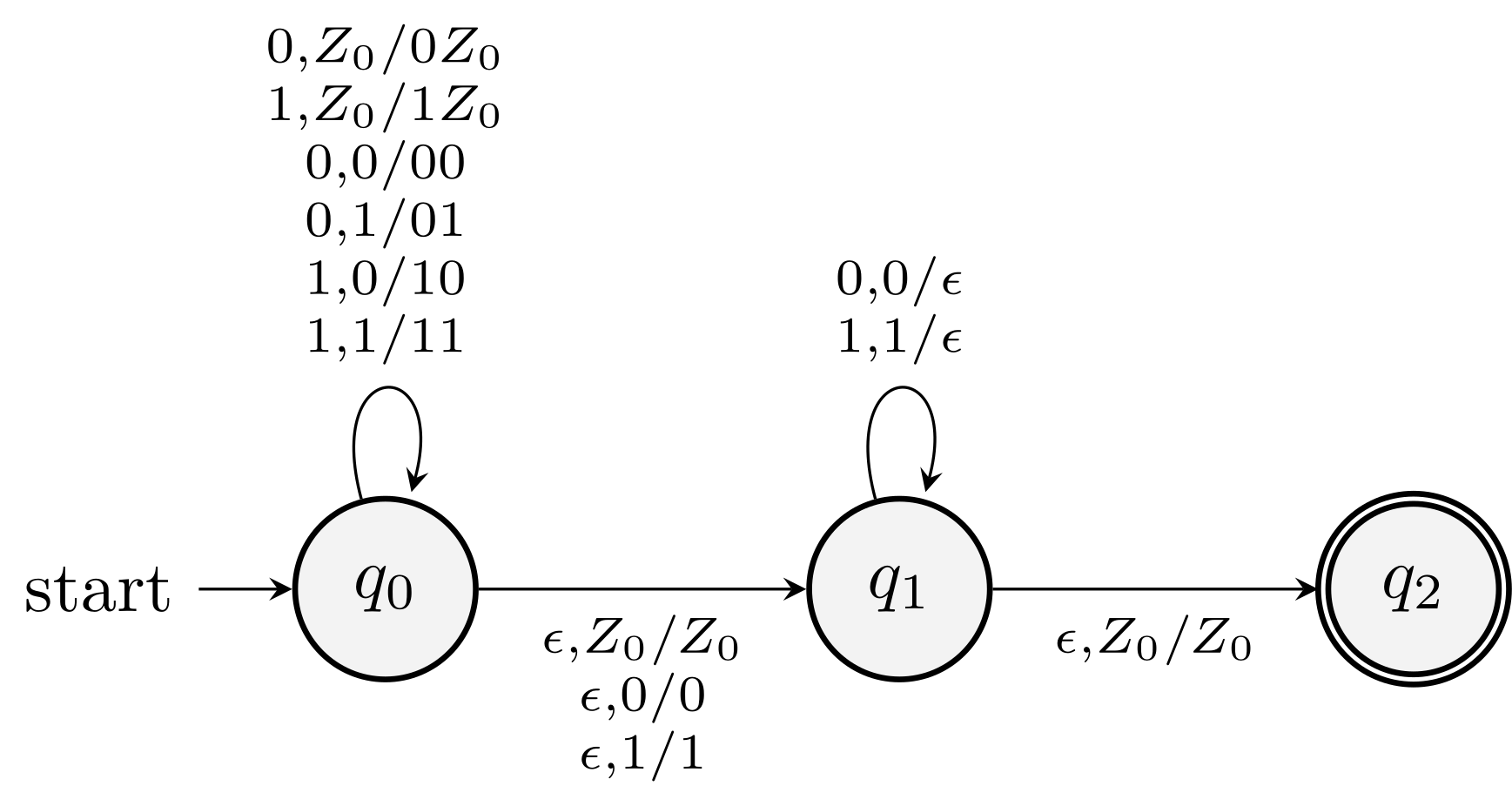

\(L_{\text{wwr}}=\{ww^R \mid w \in \{0,1\}^*\}\).

- State \(q_0\), read a symbol, and store it on the stack.

- At any time, we may guess (non-determinism) that we have seen the middle, and go to state \(q_1\).

- In state \(q_1\), we compare input symbols with the symbol at the top of the stack. Pop the stack if they match. Otherwise, this (non-deterministic) branch dies.

- If we empty the stack (or enter accepting state \(q_2\)), we have indeed seen \(ww^R\).

Formal definition

\(P = (Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, \delta, q_0, Z_0, F)\)

States, input symbols, stack symbols, transition function, start state, start symbol (initial stack), accepting states.

\(\delta(q,a,X)\) where \(q\) is a state in \(Q\), \(a\) is either an input symbol or \(\eps\), and \(X\) is a stack symbol.

\(\delta\) outputs a set of pairs \((p, \gamma)\), where \(p\) is the new state, and \(\gamma\) is the string of symbols used to replace the top stack symbol.

Example

The PDA for \(L_{\text{wwr}}\) is \[\begin{equation*} P=(\{q_0, q_1, q_2\}, \{0, 1\}, \{0, 1, Z_0\}, \delta, q_0, Z_0, \{q_2\}). \end{equation*}\]

A graphical notation for PDA's

Similar to transition diagrams for DFA's.

What's new: labels

\(a, X / \gamma\)

\(0, Z_0 / 0Z_0\)

Example (6.2 of the textbook)

How does it accept \(010010\)?

Instantaneous description of a PDA

Configuration \((q,w,r)\), ID

\(q\): current state

\(w\): remaining input

\(\gamma\): stack content

`turnstile' notation (\(\vdash\) in LaTeX)

Suppose \(\delta(q,a,X)\) contains \((p,\alpha)\). Then for all strings \(w\) in \(\Sigma^*\) and \(\beta\) in \(\Gamma^*\) we write \[\begin{equation*} (q, aw, X\beta) \vdash (p, w, \alpha\beta) \end{equation*}\]

Define \(\vdash^*\) as the reflexive transitive closure of \(\vdash\).

Three important principles about ID's:

- If a sequence of ID's is legal for a PDA \(P\), then the computation formed by adding the same additional input string to the end of the input in each ID is also legal.

- If a computation is legal, then the computation formed by adding the same additional stack symbols below the stack in each ID is also legal.

- If a computation is legal, and some tail of the input is not consumed, then we can remove this tail from the input in each ID, and the resulting computation will still be legal.

Can we remove the tail from the stack?

Theorem. If \((q, x, \alpha) \vdash^* (p, y, \beta)\), then for any string \(w\) in \(\Sigma^*\) and \(\gamma\) in \(\Gamma^*\), it holds that \[\begin{equation*} (q, xw, \alpha\gamma) \vdash^* (p, yw, \beta\gamma). \end{equation*}\]

ASK. Is the converse also true?!

Actually, it is tricky to define the converse; notice the for all quantification. There are strings that a PDA might be able to process by popping its stack, using parts of \(\gamma\). Hence the following converse does NOT hold.

Theorem (Converse candidate). Let \(w\) and \(\gamma\) be any two strings in \(\Sigma^*\) and \(\Gamma^*\) resp. If \[\begin{equation*} (q, xw, \alpha\gamma) \vdash^* (p, yw, \beta\gamma). \end{equation*}\] then \((q, x, \alpha) \vdash^* (p, y, \beta)\).

ASK. What is the difference between converse and contrapositive?

Theorem. If \((q,xw,\alpha) \vdash^* (p,yw,\beta)\), then \((q,x,\alpha) \vdash^* (p,y,\beta)\).

The Language of a PDA

Acceptance by the final state and by empty stack.

Equivalent: In the sense that \(L\) has a PDA that accepts it by state if and only if there is a PDA that accepts it by empty stack.

For a given PDA, however, two acceptance conditions may very likely be different.

Acceptance by final state

\[\begin{equation*} L(P) = \bigl\{w \mid (q_0, w, Z_0) \vdash^* (q, \eps, \alpha) \text{ for some } q \in F \bigr\}. \end{equation*}\]

The PDA in Example (6.2) accepts \(L_{\text{wwr}}\).

Acceptance by empty stack

We do not need to specify \(F\) if empty-stack acceptance is considered.

For each PDA \(P = (Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, \delta, q_0, Z_0)\), define \[\begin{equation*} N(P) = \{w \mid (q_0, w, Z_0) \vdash^* (q, \eps, \eps) \}. \end{equation*}\]

It is easy to change Example 6.2 so that it accepts by empty stack.

Instead of the transition \(\delta(q_1, \eps, Z_0) = \{(q_2, Z_0)\}\), use \(\delta(q_1, \eps, Z_0) = \{(q_2, \eps)\}\).

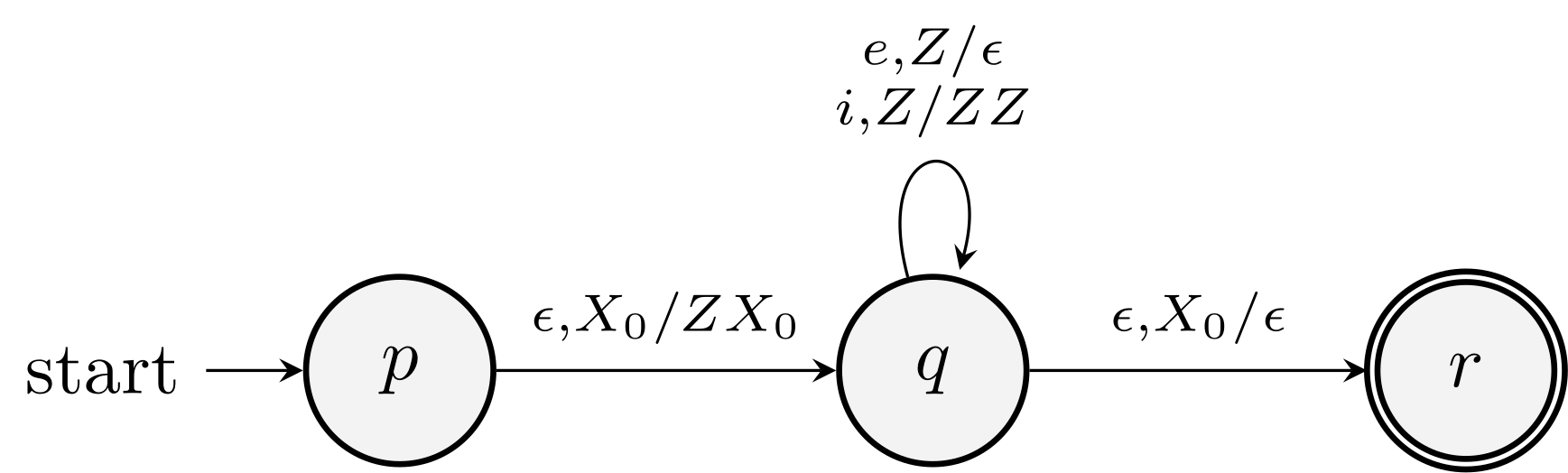

From empty stack to final state

Proof idea: Use a different initial stack symbol \(X_0\). Push \(Z_0\) as the first step. Whenever we see \(X_0\), pop \(X_0\) and enter the final state.

The full proof is a bit tedious and we omit it in class.

Example. The PDA accepts the if/else errors by empty stack and the transformed PDA that accepts the same language by final state.

From final state to empty stack

Proof idea: For all accepting final state, add \(\eps\) transition to a new state which keeps popping the stack until it's empty.

Is this valid? What could go wrong?!

A PDA that accepts by final state may accidentally empty its stack and we need to use a new initial stack symbol.

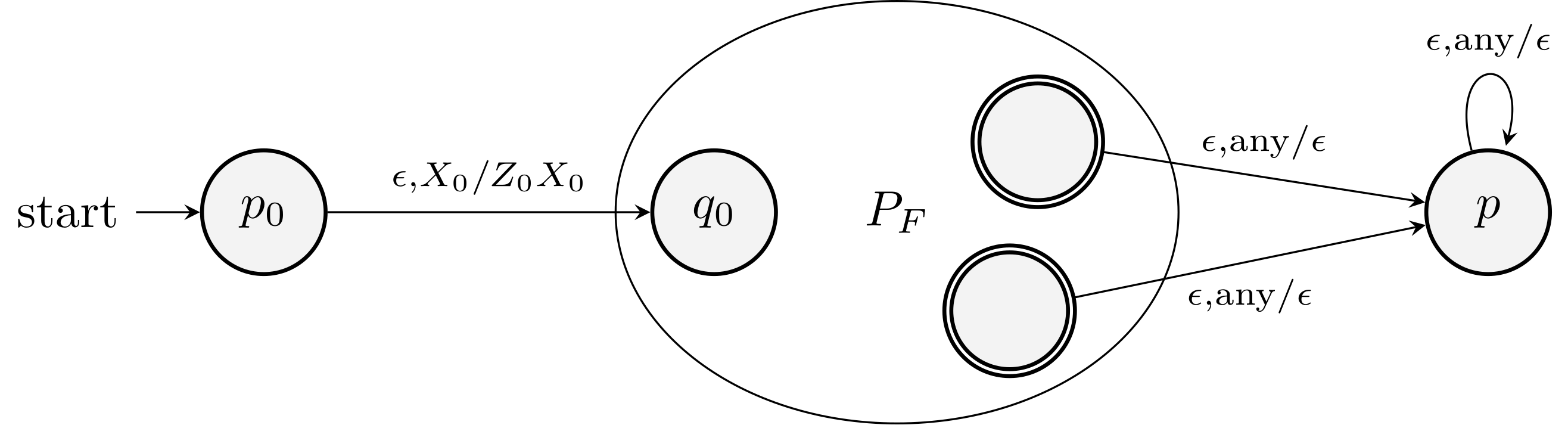

Use a new initial stack symbol to solve the problem. The construction is illustrated in the following figure.

Theorem. Let \(P_F\) be a PDA that accepts by final state. There is a PDA \(P_N\) such that \(L(P_F) = N(P_N)\).

Write the proof yourself and compare it with the textbook.

Step 1. Formally define \(P_N\). Step 2. Prove it works.

Examples

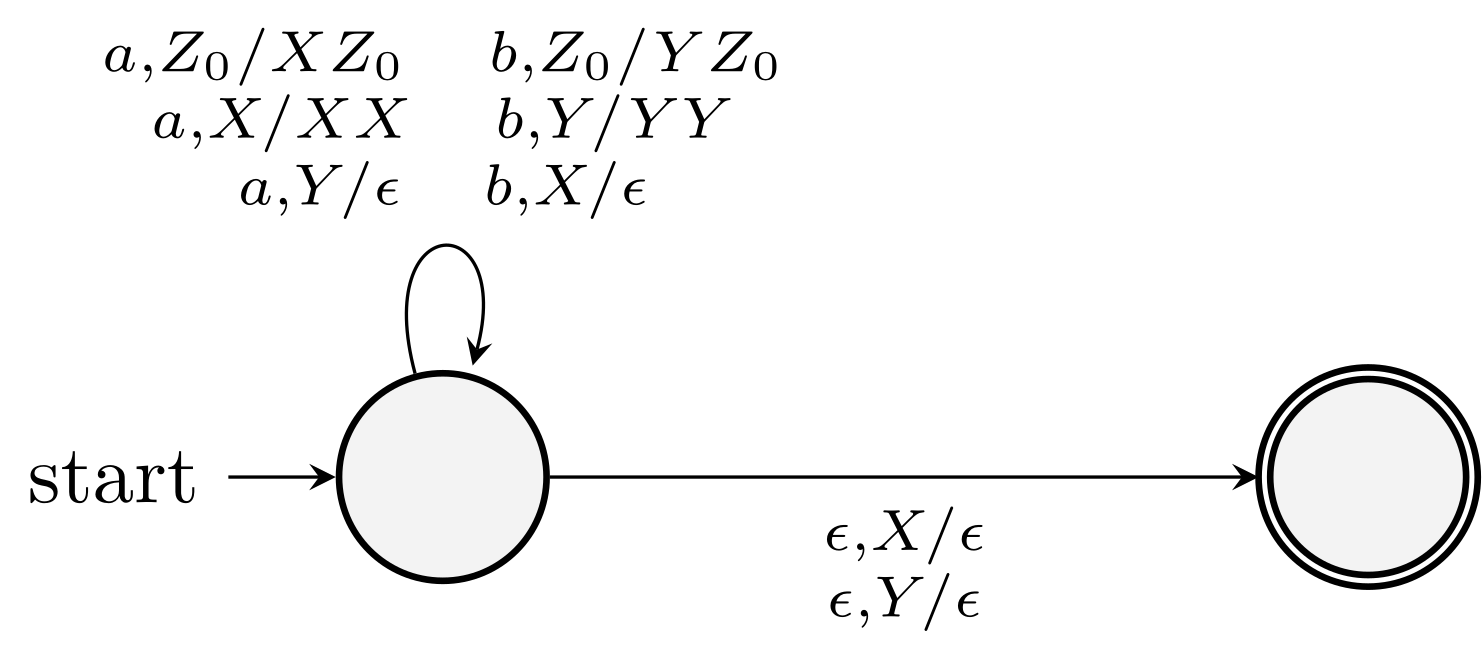

Construct a PDA that accepts \(L = \{ w \in \{a,b\}^* \mid \text{count}(a,w) \ne \text{count}(b,w) \}\).

Use two stack symbols \(X\) and \(Y\) in addition to \(Z_0\).

For \(a\) and \(X\), push \(X\). For \(a\) and \(Y\), pop \(Y\).

For \(b\) and \(X\), pop \(X\). For \(b\) and \(Y\), push \(Y\).

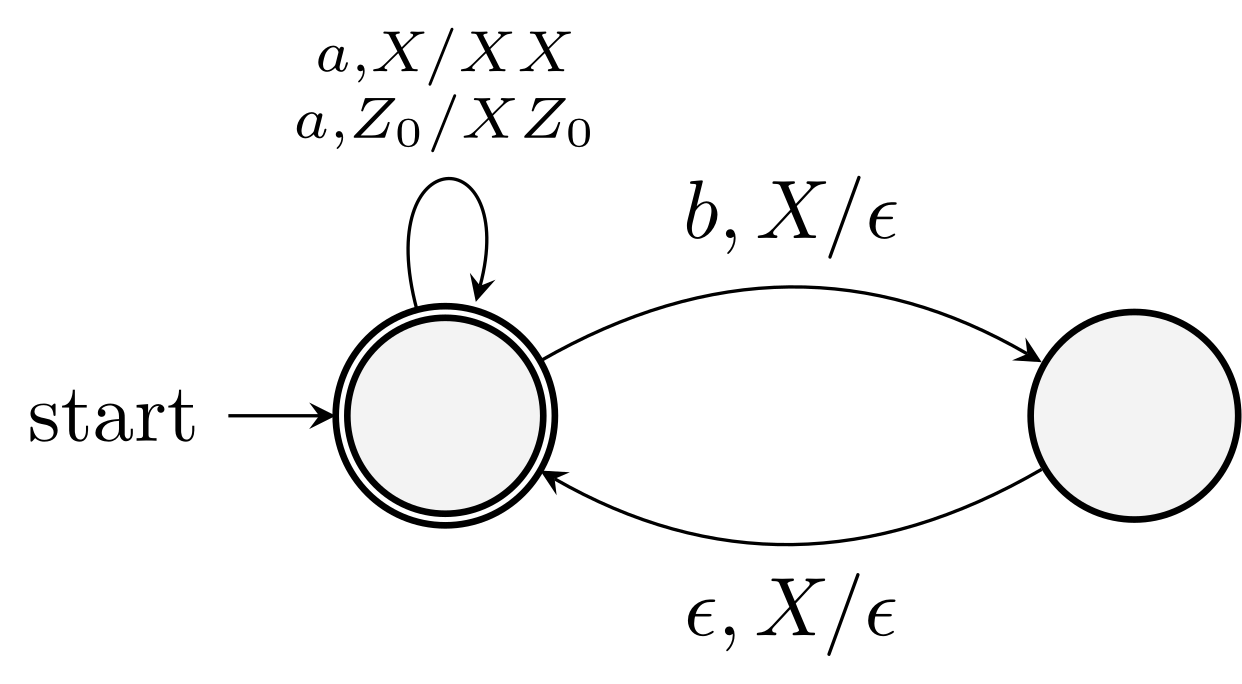

Construct a PDA that accepts strings over \(\{a,b\}\) such that the number of \(a\) is at least twice the number of \(b\) in any prefix of the string.

Consider the accepting state variant.

Push \(X\) for \(a\) and pop \(X\) for \(b\). Use \(\eps\)-move to implement the "twice" condition.

Lecture 9: Equivalence of PDA and CFG

Equivalence of PDA's and CFG's

We will prove that CFG's and PDA's accepting by empty stack are equivalent.

From grammars to PDA's

Consider a left sentential form of the grammar.

Left sentential form is a string in \((V \cup T)^*\) leftmost derivable from \(S\).

Write the left sentential form as \(xA\alpha\). We call \(A\alpha\) the tail.

If the sentential form contains terminals only, its tail is \(\eps\).

We put the tail on the stack with \(A\) at the top.

\(x\) is the consumed input.

So if \(w=xy\), then \(y\) is the remaining input.

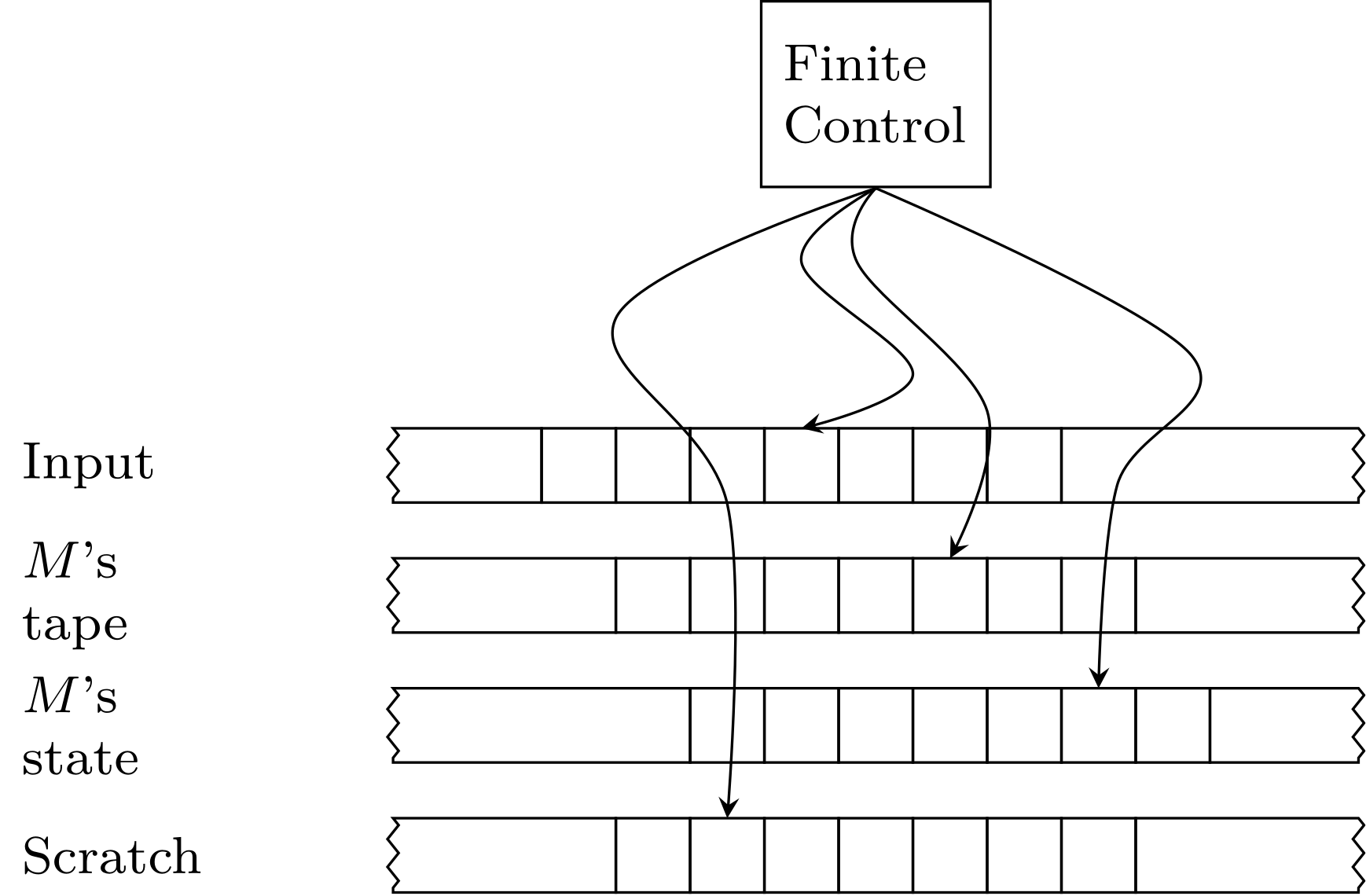

Idea: Suppose the PDA is in ID \((q, y, A\alpha)\), representing left-sentential form \(xA\alpha\). It guesses the production rule to use next, \(A \rightarrow \beta\). Enter ID \((q, y, \beta\alpha)\). If there are any terminals appearing at the beginning of \(\beta\alpha\), pop it.

How many states do we need in the above construction?

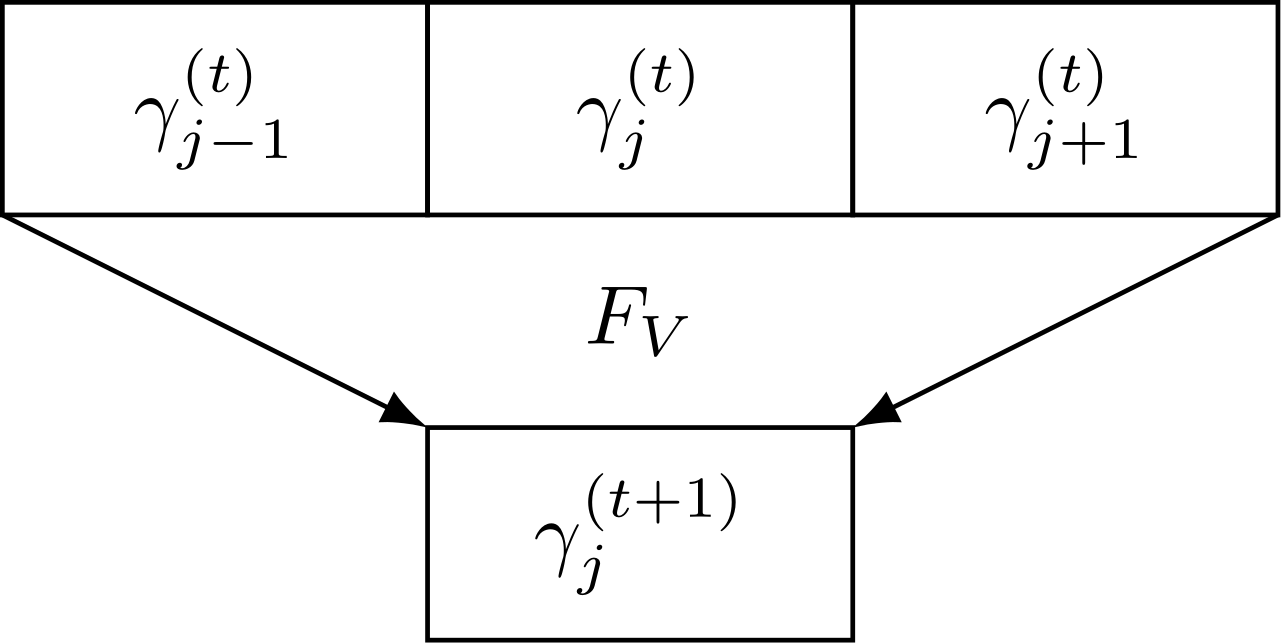

More formally, we have \[\begin{equation*} P = (\{q\}, T, V \cup T, \delta, q, S), \end{equation*}\] where \(\delta\) is defined by:

- For each variable \(A\), \[\begin{equation*} \delta(q, \eps, A) = \{ (q, \beta) \mid A \rightarrow \beta \text{ is a production of } G \}, \end{equation*}\]

- For each terminal \(a\), \[\begin{equation*} \delta(q, a, a) = \{ (q, \eps) \}. \end{equation*}\]

Theorem. If PDA \(P\) is constructed from CFG \(G\) as above, then \(N(P) = L(G)\).

Proof

We prove that \(w \in N(P)\) if and only if \(w \in L(G)\).

(If) Suppose \(w\) is in \(L(G)\). Then \(w\) has a leftmost derivation

\(S = \gamma_1 \Rightarrow_{\text{lm}} \gamma_2 \Rightarrow_{\text{lm}} \cdots \Rightarrow_{\text{lm}} \gamma_n = w\). We prove that for all \(i\), \((q,w,S) \vdash^* (q, y_i, \alpha_i)\), where \(y_i\) and \(\alpha_i\) form a representation of the left-sentential form \(\gamma_i\). That is, \(\alpha_i\) is the tail of \(\gamma_i\), \(\gamma_i = x_i \alpha_i\), and \(w=x_i y_i\).

Basis: Easy.

Induction: Prove \((q, w, S) \vdash^* (q, y_{i+1}, \alpha_{i+1})\) assuming the \(i\)-th hypothesis.

(Only If) It is the hard part. We want to prove that if \((q,w,S) \vdash^* (q,\eps,\eps)\), then \(S \Rightarrow^* w\).

Strengthen it to all (non-starting) variables and we prove that \[\begin{equation*} \text{If } (q,x,A) \vdash^* (q,\eps,\eps), \text{ then } A \Rightarrow^* x. \end{equation*}\]

Induction on the number of moves taken by the PDA.

Basis. Easy. The only possibility is that \(A \rightarrow \eps\) is used in the PDA.

Induction. Suppose the first move of the PDA corresponds to the production \(A \rightarrow Y_1 \cdots Y_k\).

The PDA needs to pop \(Y_1, \ldots, Y_k\) sequentially. More formally \((q, x_i x_{i+1} \cdots x_k, Y_i) \vdash^* (q, x_{i+1} \cdots x_k, \eps)\) for all \(i\). By induction hypothesis, \(Y_i \Rightarrow^* x_i\).

Write \(x=x_1 \cdots x_k\) where \(x_1\) is the input consumed until \(Y_1\) is popped off from the stack and so on.

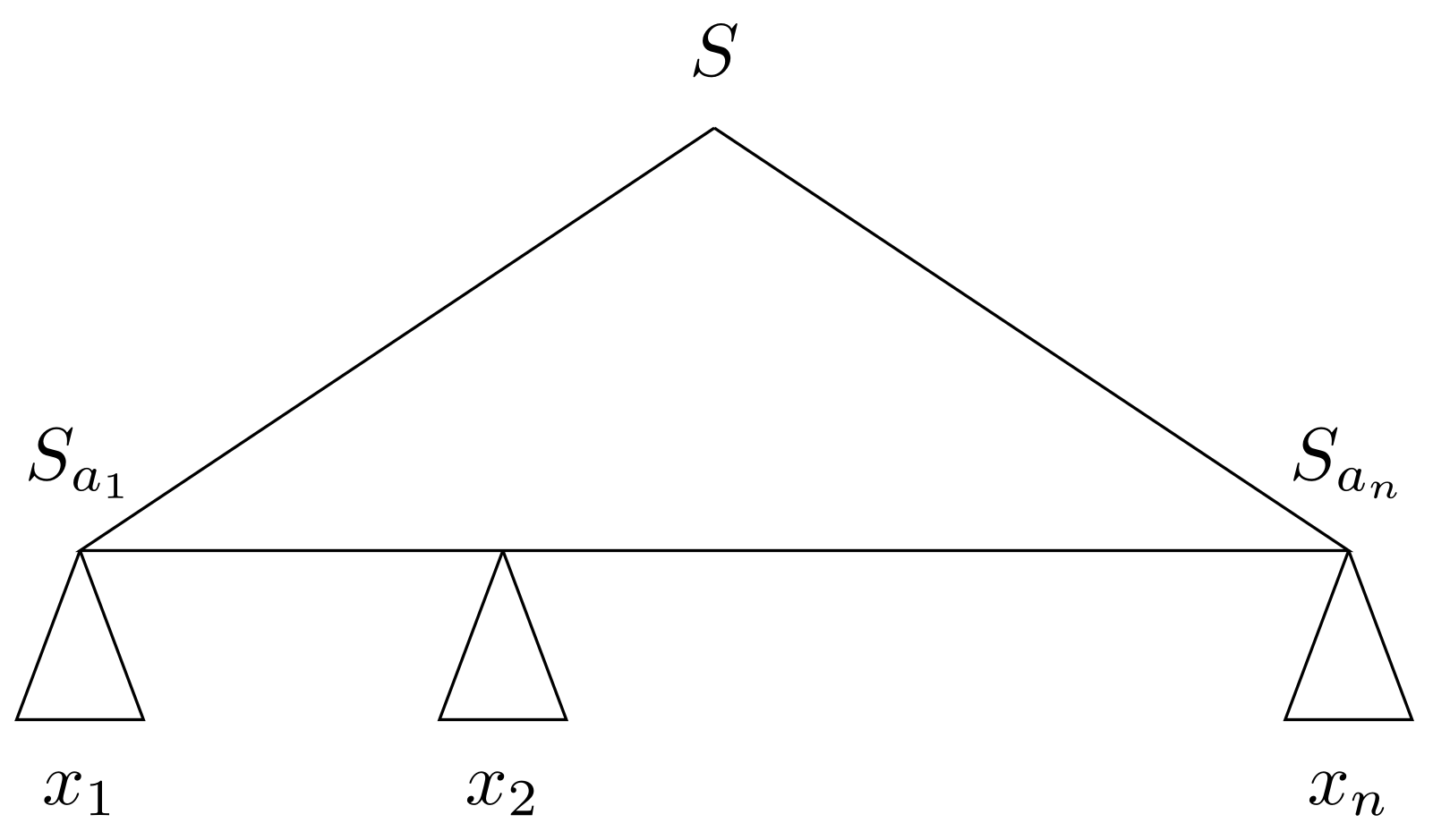

From PDA's to grammars

This is non-trivial to prove.

We have seen a very special form of PDA with one state that mimics the derivation of a CFG.

But now, the PDA may be more general.

The special PDA either matches the input and terminals or simulates a rule by the typical change of the stack.

The variables are those symbols that are not simply matched.

The general PDA also has state transitions. What should be the variables in the grammar?

- Net popping of some symbol \(X \in \Gamma\) from the stack.

- A change in state from some \(p\) at the beginning to \(q\) when \(X\) has finally been replaced by \(\eps\).

Understand how the PDA works locally using a collection of moves.

We represent such a variable by the composite symbol \([pXq]\). (It is one single variable)

Theorem (6.14 of the textbook): Let \(P =(Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, \delta, q_0, Z_0)\) be a PDA. Then there is a CFG \(G\) such that \(L(G) = N(P)\).

We construct grammar \(G = (V, T, R, S)\) as follows.

- There is a special symbol \(S\), the start symbol.

- All symbols of the form \([pXq]\) where \(p, q\in Q\) and \(X\in \Gamma\).

The production rules:

For all states \(p\), there is a production rule \(S \rightarrow [q_0Z_0p]\).

Why for all \(p\)?: \([q_0Z_0p]\) is intended to generate all strings \(w\) that cause \(P\) to net pop \(Z_0\) while going from \(q_0\) to \(p\). With acceptance by empty state, we allow all \(p\).

Let \(\delta(q, a, X)\) contain the pair \((r, Y_1 \cdots Y_k)\), where

- \(a\) is either a symbol in \(\Sigma\) or \(a = \eps\).

- \(k\) can be any number, including \(0\), where the pair is \((r, \eps)\).

Then for all list of states \(r_1, \ldots, r_k\), \(G\) has rule

\[\begin{equation*} [qXr_k] \rightarrow a[rY_1r_1][r_1Y_2r_2] \cdots [r_{k-1}Y_kr_k]. \end{equation*}\]

This is the key construction. It is special in the sense that it only contains one terminal in each rule.

Intuition: one way to net pop \(X\) and go from state \(q\) to \(r_k\) is to read \(a\), then use some input to pop \(Y_1\) off the stack while going from state \(r\) to state \(r_1\), then pop \(Y_2\) and transit from \(r_1\) to \(r_2\), and so on.

Claim: \([qXp] \Rightarrow^* w\) if and only if \((q, w, X) \vdash^* (p, \eps, \eps)\)

Proof.

(If) Suppose \((q, w, X) \vdash^* (p, \eps, \eps)\). We need to show \([qXp] \Rightarrow^* w\).

Induction on the number of steps made by the PDA.

Basis. Easy. If there is one step, \((p, \eps)\) is in \(\delta(q, a, X)\) and \(a=w\).

Induction. Suppose \[\begin{equation*} (q, w, X) \vdash (r_0, x, Y_1 \cdots Y_k) \vdash^* (p, \eps, \eps), \end{equation*}\] takes \(n\) steps in total.

We have \(w=ax\) where \(a\) could be a symbol or \(\eps\).

The PDA will need to net pop \(Y_1, \ldots, Y_k\) sequentially while consuming \(w\).

To include \(w\) in the language, the grammar needs to simulate the above procedure using derivations.

Let the state after the net popping of \(Y_1\) be \(r_1\), …

The first step above implies that \((q, a, X)\) contains \((r_0, Y_1 \cdots Y_k)\) and by our construction, \(G\) has a rule \[\begin{equation*} [qXp] \rightarrow a[r_0Y_1r_1][r_1Y_2r_2] \cdots [r_{k-1}Y_kp] \end{equation*}\]

Note that the net popping of \(Y_i\) will have less steps and the induction hypothesis applies.

(Only-If) If \(S \Rightarrow^* w\), then \(w \in N(P)\).

Induction on the number of steps in the derivation.

Basis. One step. \([qXp] \rightarrow w\) must be a production.

By the construction of the grammar, this is a production rule only if

- \(w = a\)

- \((p, \eps)\) is in \(\delta(q, a, X)\).

Induction. Suppose \[\begin{equation*} [qXr_k] \Rightarrow a[r_0Y_1r_1] \cdots [r_{k-1}Y_kr_k] \Rightarrow^* w. \end{equation*}\]

The first derivation means that \(\delta(q, a, X)\) contains \((r_0, Y_1 \cdots Y_k)\).

Write \(w = a w_1 \cdots w_k\) and \([r_{i-1}Y_ir_i] \Rightarrow^* w_i\). Use induction hypothesis.

(The principles of extending the remaining input and stack will be used.)

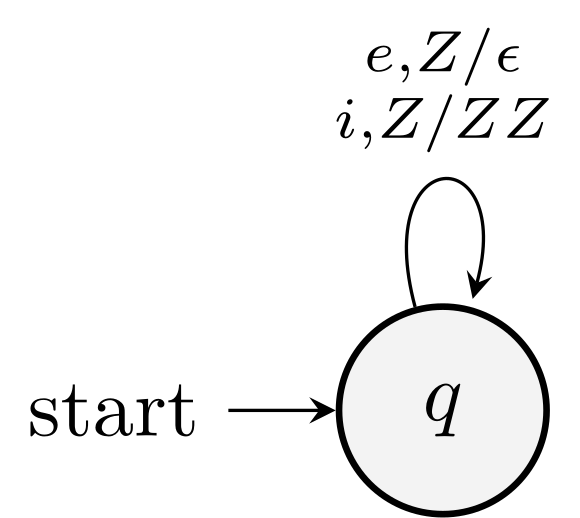

Example

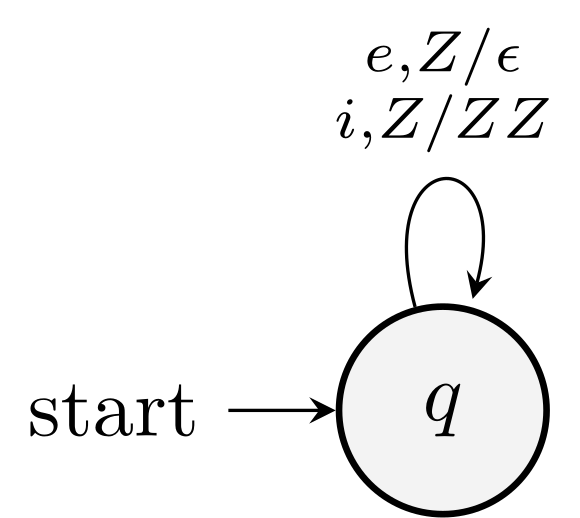

Convert PDA \(P = (\{q\}, \{i, e\}, \{Z\}, \delta, q, Z)\) to a grammar (PDA in Example 6.10).

\(S \rightarrow [qZq]\)

As \(\delta(q, i, Z)\) contains \((q, ZZ)\), we get production \([qZq] \rightarrow i [qZq] [qZq]\). In this simple example, we have one such rule, if the PDA had \(n\) states, we would need \(n^2\), as the middle two and the last \(q\) should run over all possible states.

As \(\delta(q, e, Z)\) contains \((q, \eps)\), we get production \([qZq] \rightarrow e\).

Rename \([qZq]\) as \(A\), we have

- \(S \rightarrow A\)

- \(A \rightarrow i A A | e\)

As \(S\) and \(A\) derive the same language, we can write the grammar as \(S \rightarrow iSS | e\).

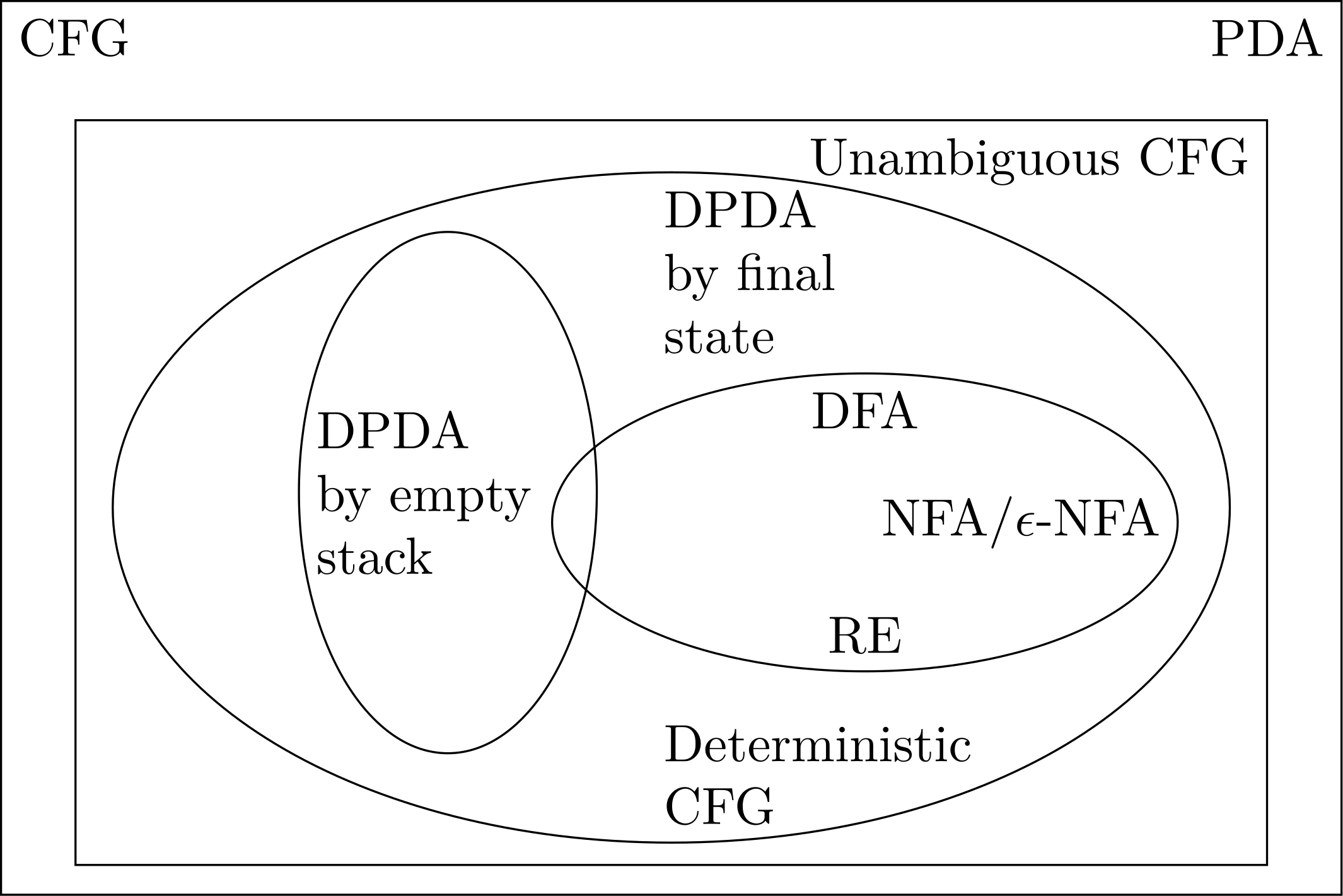

Deterministic PDA

PDA is by definition non-deterministic.

In this part, we study a deterministic variant of PDA's.

Useful for modeling parsers.

Definition

- A PDA is deterministic if

- For all \(q, a, X\), \(\delta(q, a, X)\) is empty or a singleton.

- If there is a \(a \in \Sigma\) such that \(\delta(q, a, X)\) is not empty, then \(\delta(q, \eps, X)\) must be empty.

Properties

DPDA's accept languages that is between RL's and CFL's.

Theorem. Any regular language has a DPDA.

There is a non-regular language (say, \(L_\text{wcwr}\)) accepted by DPDA. So DPDA's are more powerful than FA's.

\[\begin{equation*} L_{\text{wcwr}} = \bigl\{ wcw^R \mid w \in \Sigma^* \bigr\} \end{equation*}\]

However, DPDA's with empty stack acceptance are quite weak.

Theorem. A language \(L\) is in \(N(P)\) for some DPDA \(P\) if and only if \(L\) has the prefix property (no two strings \(x, y\in L\) and \(x\) is the prefix of \(y\)) and \(L\) is \(L(P')\) for some DPDA \(P'\).

DPDA's are weaker than PDA's.

Examples

\(L_\text{wcwr}\) does have the prefix property.

\(L(0^*)\) is regular but does not have prefix property.

\(L_\text{wwr}\) cannot be accepted by any DPDA's (even with final-state acceptance).

Proof idea: Suppose \(P\) has seen \(n\) \(0\)'s and then sees \(110^n\). It must verify that there were \(n\) \(0\)'s after the \(11\) and to do so it must pop its stack. So the PDA will not be able to act differently for two cases of further remaining inputs \(0^n110^n\) (should accept as \(w=0^n110^n\)) and \(0^m110^m\) (should reject if \(m\ne n\)).

DPDA and Ambiguity

Languages accepted by DPDA's are unambiguous.

Yet DPDA languages are not exactly the subset of CFL's that are not inherently ambiguous. (Example \(L_{\text{wwr}}\)).

Theorem. If \(L = N(P)\) for some DPDA \(P\), then \(L\) has an unambiguous CFG.

The construction we used for PDA to CFG will lead to unambiguous CFG. Note that \(\delta(q, a, X) = \{(r, Y_1 \cdots Y_k) \}\) may lead to multiple productions in \(G\). But as \(P\) is deterministic, only one will be consistent with what \(P\) actually does.

Theorem. If \(L = L(P)\) for some DPDA \(P\), then \(L\) has an unambiguous CFG.

Endmarker trick. Treat \(\$\) as a new variable and add \(\$ \rightarrow \eps\)!

Summary of Languages Studied

Lecture A: Properties of Context-Free Languages

Normal Forms for CFG

Chomsky Normal Form

Every CFL (without \(\eps\)) has a CFG whose rules have the form \(A\rightarrow BC\) or \(A\rightarrow a\).

Some preliminary simplifications:

- Eliminate useless symbols, variables or terminals that do not appear in any derivation of a terminal string.

- We must eliminate \(\eps\) productions, those of the form \(A \rightarrow \eps\).

- We must eliminate unit productions, those of the form \(A \rightarrow B\).

Eliminating useless symbols

What symbols do not appear in any derivation of a terminal string?

What is your suggestion? Reachability?

Example: Consider the grammar

- \(S \rightarrow AB \,|\, ab\)

- \(A \rightarrow a\)

\(X\) is useful for a grammar \(G\) if there is some derivation of the form \(S \Rightarrow^* \alpha X \beta \Rightarrow^* w\).

So, in addition to reachability from \(S\), we also require \(X\) to be generating, that is \(X \Rightarrow^* w\) for some \(w\).

If we (1) eliminate symbols not generating and then (2) those not reachable, we will (proved after) have only useful symbols left.

The order matters. Consider the example above.

\[\begin{equation*} G \overset{\text{(1)}}{\longrightarrow} G_2 \overset{\text{(2)}}{\longrightarrow} G_1. \end{equation*}\]

Theorem (7.2). Let \(G\) be a CFG such that \(L(G) \ne \emptyset\). Let \(G_2\) be the grammar obtained by eliminating symbols not generating. Let \(G_1\) be the grammar obtained by eliminating symbols not reachable from \(G_2\). Then \(G_1\) has no useless symbols, and \(L(G_1) = L(G)\).

Suppose \(X\) is a symbol that remains in \(G_1\). We know \(X \Rightarrow^*_G w\) for some w. Since all symbols involved in this derivation are generating, we have \(X \Rightarrow^*_{G_2} w\). Since \(X\) is not eliminated in the second step, we know that \(S \Rightarrow^*_{G_2} \alpha X \beta\). Since every symbol used in this derivation is reachable, we have \(S \Rightarrow^*_{G_1} \alpha X \beta\), showing \(X\) is reachable in \(G_1\).

As \(\alpha X \beta\) contains only symbols in \(G_2\), which are generating by definition, we have \(\alpha X \beta \Rightarrow^*_{G_2} xwy\). This means that all symbols in \(xwy\) are reachable from \(S\). Thus, this derivation is also a derivation of \(G_1\). So \(S \Rightarrow^*_{G_1} \alpha X \beta \Rightarrow^*_{G_1} xwy\), and \(X\) is generating in \(G_1\).

It is easy to show \(L(G) = L(G_1)\) and we omit the proof.

Finding generating and reachable symbols

Both are easy; we use finding generating symbols as an example.

Basis: All symbol in \(T\) is generating.

Induction: If \(A \rightarrow \alpha\) is a production rule, and all symbol in \(\alpha\) is generating, then so is \(A\). This rule includes \(A \rightarrow \eps\).

This works as 1) all symbols found this way are generating, and 2) all generating symbols can be found in this way.

Eliminating \(\eps\)-productions

We will show \(\eps\)-productions are not essential.

Theorem. If \(L\) has a CFG, then \(L - \{ \eps \}\) has a CFG without \(\eps\)-production.

A variable \(A\) is nullable if \(A \Rightarrow^* \eps\).

If \(A\) is nullable and appears in a production body of, say, \(B \rightarrow CAD\), we add a rule \(B \rightarrow CD\) alongside \(B \rightarrow CAD\) (do not allow \(A\) to derive \(\eps\)).

Find nullable symbols iteratively.

Basis. If \(A \rightarrow \eps\) is a rule, then \(A\) is nullable.

Induction. If there is a rule \(B \rightarrow C_1 \cdots C_k\) and each \(C_i\) is nullable, then \(B\) is nullable.

Theorem. The above procedure finds all the nullable symbols.

Eliminating \(\eps\)-productions.

First, find all nullable variables. For a rule \(A \rightarrow B_1 \cdots B_k\) if \(m\) of the \(k\) variables are nullable, consider \(2^m\) replicates of the rule removing all possible combinations of the nullable variables.

There is one exception when \(m=k\) as we don't include the case when all variables are \(\eps\). And we do not keep any \(A \rightarrow \eps\).

Example

Consider grammar

- \(S \rightarrow AB\)

- \(A \rightarrow aAA \,|\, \eps\)

- \(B \rightarrow bBB \,|\, \eps\)

Resulting grammar

- \(S \rightarrow AB \,|\, A \,|\, B\)

- \(A \rightarrow aAA \,|\, aA \,|\, a\)

- \(B \rightarrow bBB \,|\, bB \,|\, b\)

Proof

The proof is a bit tedious. Inductively prove a stronger statement:

\[\begin{equation*} A \Rightarrow^*_{G_1} w \text{ iff } A \Rightarrow^*_G w \text{ and } w\ne \eps. \end{equation*}\]

Eliminate unit productions

Productions like \(A \rightarrow B\) where \(B\) is a variable.

Unit pairs: \((A, B)\) such that \(A \Rightarrow^* B\) uses unit productions only.

Computation of unit pairs.

Basis. \((A, A)\) is a unit pair for all \(A \in V\).

Induction. \((A, B)\) is a unit pair, and \(B\rightarrow C\) is a production, then \((A, C)\) is a unit pair.

Claim: The above procedure computes all unit pairs.

Eliminate unit productions:

- Compute all unit pairs

- For all unit pairs \((A, B)\), if \(B \rightarrow \alpha\) is not a unit production, add \(A \rightarrow \alpha\) to \(G_1\).

- Add all non-unit productions of \(G\) to \(G_1\)

Example

- \(S \rightarrow A\)

- \(A \rightarrow 0BD \,|\, 0B\)

- \(B \rightarrow 0BC \,|\, 1\)

- \(C \rightarrow 1\)

Unit pairs \((A,A)\), \((B,B)\), \((C,C)\), \((D,D)\), \((S,S)\) and \((S,A)\)

After elimination, we have

- \(S \rightarrow 0BD \,|\, 0B\)

- \(A \rightarrow 0BD \,|\, 0B\)

- \(B \rightarrow 0BC \,|\, 1\)

- \(C \rightarrow 1\)

CFG simplification